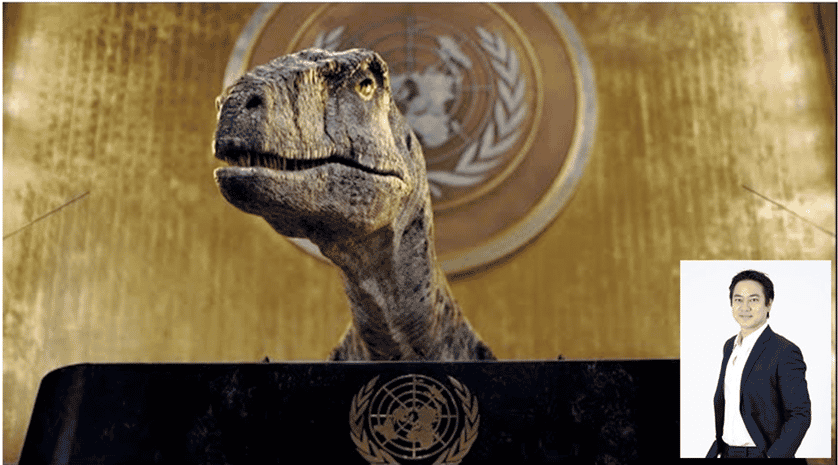

“Don’t choose extinction” says the dinosaur. And me in the bottom-right corner.

Late last year the UN released a YouTube video of a talking dinosaur, voiced over by Jack Black, giving a speech at the UN General Assembly. It warned of the threat of climate change to humanity. The message was clear: Unless humans confront it, we’ll end up like the dinosaurs.

A month before that the K-pop BTS band had performed at the General Assembly. I could never imagine those things at the UN in the old 60s or 70s conservative days. This got me pondering about the role of the UN in the 21st century. Is it still relevant? Is it effective and powerful? Does it better the lives of the nearly eight billion humans on the planet? Since this year marks the 77th year of the UN, I’m going to address these questions.

Let’s go back in time. WW2 was the biggest conflict in human history, involving over 30 countries, Thailand included. Seventy million lives perished. The heaviest casualties were suffered on the Eastern Front between the Nazis and the Soviets and in China by the Japanese Imperial force, led by Emperor Hirohito. The carnage, the destruction, and the senseless killings were so bad that the world leaders at the time Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and Joseph Stalin met up at Yalta Conference and vowed to prevent another global war. Which eventually led to the establishment of the UN, the successor of the League of Nations. In short, it was to stop WW3 – the complete annihilation of humanity. How? Through cooperation from every country on the planet. It was such a noble goal, a huge vision. No organisation in the entire human history had done it before. Not the Mongols nor the Roman emperors. (Unfortunately, no Boeing aircraft had existed to fly the Romans to meet other leaders across the ocean.)

Macrowar & Microwar

Strictly speaking, if the KPI of the UN was simply preventing WWIII where dozens of countries are killing each other, then the UN has achieved its stated goal. The Cold War could have turned into a “hot war”, resulting in WWIII. Thank god it didn’t. Since then, despite dozens of regional and within-country conflicts (what I call “microwars”), the world has never witnessed another world war.

The UN has six organs or functional parts: General Assembly, Secretariat, Security Council, International Court of Justice, Economic and Social Council, and Trusteeship Council. The most important council is, without a doubt, the Security Council. For it’s the only council whose decisions are binding on members. It has the power to apply economic sanctions on a target country or send in UN peacekeeping force. Crucially, it’s where the five winners of WWII are the permanent council members with vetoing power. All it takes is for one permanent member to veto to kill a motion. Metaphorically, it’s like driving a car with five drivers. Each wanting to hit the brake pedal as he/she pleases. The result? The car doesn’t move much.

Within these six organs are dozens of agencies under them such as the World Health Organisation (WHO), World Trade Organisation (WTO), IMF and UNICEF. It is a huge inter-governmental organisation with many tentacles, in other words, employing approx. 50,000 officers in 193 countries, with a total budget for all agencies $50 billion per year.

Challenges and lateral-thinking proposed solutions

So, what are some of the problems in the UN? As I alluded to, the vetoing power almost guarantees that necessary actions could not be taken. Russia annexing Crimea? Russia will veto any actions the UN takes. Israelis occupying Palestine? The US will veto to protect Israel – “BFF” best friends forever. Myanmar generals killing ethnic minorities and their own citizens? China will veto any ‘interference’. Thus, on any issue/motion, there is bound to be at least one permanent member whose interest is affected enough to shoot down the motion.

By the UN records, the Grizzly Russia has vetoed 188 times since the founding of the UN, followed by the US at 82. The remaining three have each used vetoes fewer than 30 times. To be fair to Russia, most of their vetoes were used during the Cold War before the 1990s.

My suggested solutions are: (1) Discard the vetoing power altogether, leaving the decision to the security council of 15 members (5 permanent + 10 non-permanent) via a simple majority vote. This shifts the dynamic from one party stopping the motion to persuading eight or nine council members to take necessary action. (2) Since I’m already hearing the five permanent members yelling at me from New York headquarters – the only unanimous decision they could agree on – another solution is to cap the number of vetoing privileges, for instance to three per year for each permanent member. There are other solutions, to be sure. My point is to nudge for change and to make veto scarce and costly, used only when necessary.

The second problem is the UN peacekeeping force. Or should I say “Monitoring Officers” because that’s all they can really do. Since the UN doesn’t have its own military force, it relies on state members to contribute. Read this carefully: UN peacekeepers can go to conflict zones but aren’t allowed to shoot or neutralise hostile parties to save the innocents. During the Rwanda genocide, it was heart-wrenching to learn that the peacekeepers could do nothing when the Hutu majority were literally hacking the Tutsi minority to death, and raping their women. One account cited that the UN officers were told to escort foreigners to the airport, leaving the civilians behind, despite their cries and pleas. En-route to the airport, one officer said that he saw an on-coming truck full of Hutu men and teens armed with machetes and knives. He knew those civilians’ fates he left behind were sealed. And there was nothing he could do about it. This is a disgrace and an utter failure on the UN’s part.

Complicating this matter is the fact that most of the UN peacekeepers are from developing countries. The top three peacekeepers by numbers are Bangladesh, Nepal, and India, contributing between 5,000 – 6,000 troops each. And these men will listen to their respective Ministry of Defense, not the UN commander. The reality is that the rich countries fund most of the peacekeeping costs, while the poor countries chip in manpower.

My proposed solutions: Either get rid of peacekeepers altogether or give them power to enforce law-and-order in conflict-zone. “I don’t want my men to be shot by a war we play no part in,” I hear you say, general. My answer: To be part of the UN means to uphold global responsibilities which surpass national interests. If you aren’t ready to go into battle your nation isn’t responsible for, then why join the UN? Or do you prefer to exacerbate the problem by exploiting the vulnerable victims in conflict-zone like in Haiti?

Another solution is to have a small full-time professional UN force, highly trained and equipped. They can enter conflict zones within 24 hours to prevent on-the-ground carnage. Drones will be used to monitor the situation as well as warnings of transgression on both sides. Take half the funding from peacekeepers and invest in a full-time UN elite force, who shall receive orders only by UN commanders. “We can’t be taking sides!” you retort. My answer: The point is to get both sides to a conflict to stop violence and negotiate. This isn’t taking sides. It’s cooperation.

The UN’s autonomous peacekeeping robots in 2070, built by “UN Robotics Lab”?

The third problem is funding. Without members’ financial contributions, the UN will not survive. The largest contributor to the UN is the US – about 1/5 of the UN’s entire budget. Second is China (12%), third is Japan (8.5%). While I appreciate the US’s contribution to the UN, they also have an oversized influence on the UN and its agencies, as well as over smaller countries. Should the country paying the most have the most say? Plus it’s difficult to follow the money trails. Something to think about.

Overall, the UN has admirable goals. I’m not discounting most of the good work they have done. But at present, it’s more of a global forum than a tiger ready to pounce on dictators, anarchists, and non-state threats. 193 countries do make a lot of noises and are rather slow to arrive at decisions, invariably. Will national sovereignty always trump the UN? Will I see the UN Robocops patrolling the world soon? Let’s just say it’s easier to make another Robocop film than to see that happening.