Mew and Tong sit in a backyard festooned with faerie lights, knees grazing under the garden table. “After hearing [my song], do you have anything to say?” Tong hesitates but wraps his arm around Mew. They stay like that for a while, the tension in Mew’s chest expanding like a water balloon.

Finally, Tong confesses, “I don’t know.” Mew looks up, wanting to comfort Tong, but his breath catches. Tong’s eyes have darkened, his eyes trained on Mew’s. Tong draws closer — their noses brush — and closer; the balloon bursts. For twenty-three uninterrupted seconds, the two childhood friends say all they need to say.

Courtesy of Netflix, Love of Siam (2007).

In the public imagination of romantics everywhere, the outdoor, nighttime confession is an undeniable fixture. And now, here it was, played out on the big screen in Love of Siam (2007). In every screening that year, the audience held a collective breath, whether out of shock or disgust or pure adoration. This scene, after all, left no plausible deniability of the queerness of the protagonists. It cemented Love of Siam as one of the first mainstream Thai films to show a romance between two male leads.

Fifteen years after its release, I sat down with Witwisit “Pchy” Hiranyawongkul, the actor who played Mew, to discuss the film’s legacy, and the new generation of gay love stories as told through Y series.

Y series (or series wai) is a genre centred on romantic male-male relationships. Derived from the Japanese yaoi (“boys’ love”) genre, Y series are largely marketed towards young female audiences. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Rowena: Take us back to 2007. What did LGBTQ+ representation look like when you took on this role?

Pchy: At that time, most LGBTQ+ roles were comic relief characters. For this role, though, I knew the director since he was an alumnus of my school. I had seen some of his work before, so I trusted him. But of course, I was still thinking about the feedback. None of us knew if there would be consequences or controversy so we were worried. Even the memorable kiss scene, the one that people still talk about today, there were alternative takes where it was just kissing on the cheek. I think that emphasises what it was like back then.

Rowena: And what was the feedback like?

Pchy: Being gay was like an inconvenient truth in society and even within the family. Nobody wanted to talk about it. So, when this movie came out, it was ground-breaking because it became something they couldn’t avoid. I heard from so many audiences that they were able to have a conversation openly with their family. There were so many times that the audience came up to us and said: This is my story.

Rowena: Your character especially struck a chord with people, not just in Thailand but abroad too. I remember as a kid, watching you on Chinese variety shows.

Pchy: One of the things I heard from audiences is that my character represents loneliness. Being alone, living alone, striving alone. In China, I think it resonated because of the one-child policy. You were always competing with other kids from other families. You felt like no one really understood you. And then if you were LGBTQ+, it was another thing that isolated you because you couldn’t even tell your close friends or your family. So I think when my character had that monologue about loneliness, audiences felt like, oh my god! I was listened to, I was heard!

Courtesy of IMDB, Love of Siam (2007).

Rowena: Nowadays, romance plotlines between male leads are pervasive in Thai media. What do you think draws people to this genre?

Pchy: I think it’s escapism. Before Y series, people were obsessed with yaoi manga. And then, there was the emergence of idol culture. What used to be imagined romances between characters on paper or people in a band are now live motion. And, it has become industrial. Companies look at the demand and see that Y series can make money.

Rowena: The Y series industrial complex; there’s a discernable pipeline to fame now.

Pchy: It’s like artist development. They’re thinking: when this couple is done, who will be next? It’s an opening door for young, aspiring actors, the first step in the entertainment world. Because once you do this, you can be certain that there will be fans who would pay a lot of money to support you. And after you do this role, you’re free to select whatever role you want.

Rowena: I have to imagine that many of the actors in Y series are not actually LGBTQ+.

Pchy: It’s interesting from the perspective of the producer. When casting two boys, they don’t want people who are more flamboyant or more feminine. It has to be two boys who are pretty similar in masculinity. So, even though you’re making a show under the umbrella of LGBTQ+, you’re appropriating the culture — not even the culture, just the nature — for the story.

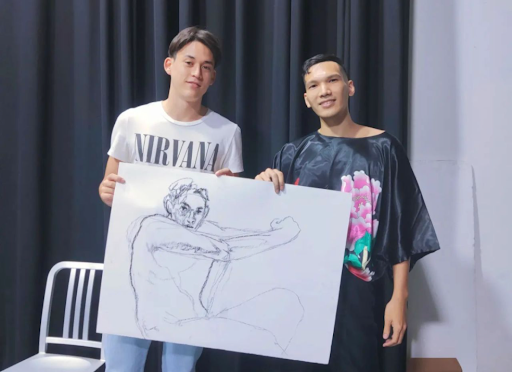

Oat Montien joins the dialogue. Oat is a nude artist, LGBTQ+ activist, and the owner of the Bodhisattava Gallery, the first LGBTQ+ art gallery in Thailand. He recently played the art teacher in the hit Y series, Not Me (2021), and brought his expertise and experiences to the set.

Courtesy of Oat Montien.

Rowena: What we’re getting at is pretty much the crux of the Y series criticism. Y series have the trappings of LGBTQ+ representation, but none of the real-life implications.

Oat: Y series benefit from us a lot, but they don’t reflect the reality of our community. We are still fighting for our rights, and there are still very real issues in our community. We can’t get married. We can’t have healthcare. We can’t sign legal documents for our partner. There are so many stories that I can tell you of people I know personally who lived together for 50 years, and then when their partner passed away, everything went back to the parents who had kicked them out of the house for being gay.

Rowena: The Y series that you’re a part of, Not Me (2021), has been lauded for actually addressing LGBTQ+ issues and other social issues like disability rights, political corruption, and privilege. The director, P’Nuchy, is a trans woman whose previous works engage with these topics too. What was it like to work on this show?

Oat: I think one of the main reasons that this particular series is so successful is that it tackles politics and reflects current events. In the finale, they have a scene where the activists and the fighters for justice are abducted. That’s such a brave thing to put that in the mainstream, and I think that’s why Not Me has been so well-received. It’s like a new chapter for the Y series genre.

Rowena: In the nude drawing scenes between Yok and Dan, those are actually your hands and your work. Your work is so intertwined with the intimacy of male nude drawings.

Courtesy of OtakuArt, Not Me (2021).

Oat: P’Nuchy gave me so much freedom and credit in changing the script to fit my practice and my aesthetic. And even the emotions, which I find so important when portraying intimacy. What does the model feel? How does the intensity build? Is there sexual tension? Is there intimacy in how you feel vulnerable? As queer people, intimacy can be very complicated. To be openly yourself, there’s a lot of fear. A fear of rejection, a fear of vulnerability, a fear as a marginalised group. So I think it was very important that she let me contribute to what queer intimacy looks like.

Rowena: Funny what happens when LGBTQ+ people are actually involved on set, both in front of the camera and behind.

Oat: And it wasn’t just me. P’Nuchy included so many iconic people in the LGBTQ+ movement. Dan’s drawings are from another LGBTQ+ artist, Baphoboy. His work is all about the conflict of power in Thailand. He used to be in the military and experienced sexual harassment in a military camp, so a lot of his work is about that. And then there’s the protest scene–

Rowena: Episode 7, the marriage equality rally–

Oat: The people speaking on stage are actually prominent queer activists. So you know, it doesn’t feel like a gimmick. These are the real people behind the real fight.

Courtesy of ABS-CBN News, Not Me (2021).

Rowena: We’re living in a post-Love of Siam, post-I Told Sunset About You, and we’re about to enter a post-Not Me world. What types of stories do you hope to see in future Y series?

Pchy: It’s a start. But what’s next? Right now, in other countries, queerness is already not just about sexuality. Queerness is also about space. When you feel isolated, regardless of sex, regardless of anything, when you’re not included… that’s already queerness, isn’t it? I hope that in the near future, we will talk about queerness in terms of being the “other,” and elevate those experiences too.

Oat: I hope that we will have entertainment — be it TV series or movies — that reflects human relationships in a diverse, accepting, and inclusive way, without having to censor things for heteronormative comfort. I hope that in the future, we can tell our story openly and honestly, and when we do, people are ready to listen and embrace it.

Support Marriage Equality: Support1448.org

Featured Artists:

Pchy: @pchysomething

Oat Montien: @oatmontienstudio & @bodhisattava.gallery

Anucha Boonyawatana: @anuchyfilm

Baphoboy: @baphoboy

Featured Works:

Love of Siam (2007)

I Told Sunset About You (2020)

Not Me (2021)

About the Author: Rowena Chang is a Fulbright Scholar interning at CityLife. She loves books, pop culture, and rambling about her latest Wikipedia rabbit hole to unsuspecting bystanders.