Upon first sighting, Dr. Hans Bänziger appears frail, with his svelte and slightly gaunt build. But all that first impression nonsense is dispensed with at the crushing moment of the firm grip of his handshake. This wiry 71 year old Swiss entomologist is no wilting scientist. In fact, he has spent the better part of the past fifty years trekking the north of Thailand’s mountains and climbing its trees to dizzying heights. He is the world expert on tear and blood sucking moths among a bewildering array of other insects and plants.

Bänziger was born and grew up in Italy, but kept his parents’ Swiss nationality. His early love of collecting butterflies led him to study entomology at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zurich, one of Europe’s leading universities. “From a young age I was fascinated by butterflies and insects; they are simply beautiful,” said Bänziger during our interview at his house surrounded by large trees and lush plants in shady Chang Khian.

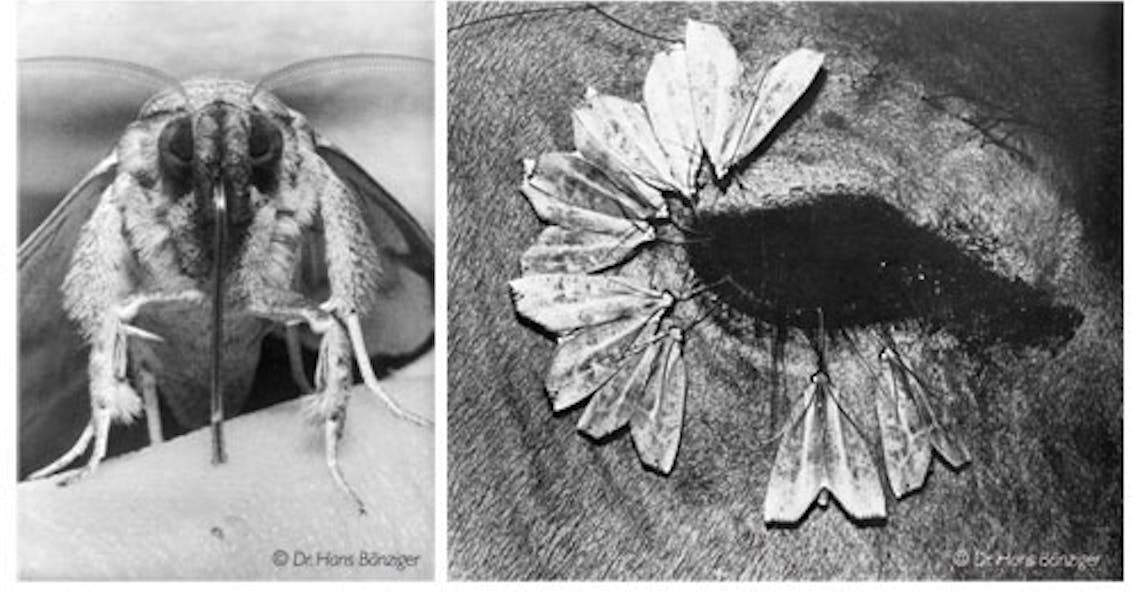

In 1965, during his studies, Bänziger came to Thailand on a UNESCO progamme to study tear sucking moths. Like many entomologists, he had longed to visit the tropics where biodiversity promised untold and unfound treasures. His two-year field research took him all over Thailand and down to Malaysia, where he made a remarkable discovery. “In the jungles of Malaya I found that there was a moth which pierced the skin of large mammals and actually sucked blood.”

With his find in his metaphoric pocket, he returned to Switzerland to finish his doctorate, following which he received a Swiss scholarship, which amounts to a post-doctorial grant today, to return to Thailand as well as Malaysia and Indonesia. “I had to take my research further, there were so many questions left unanswered,” said Bänziger with contained excitement he appears to reserve for insect-speak. “I had to find out what animals this moth, a species of Calyptra, attacks; as it turns out they were elephants, buffaloes, deer and other large mammals. I then captured the moths and took them to a lab where I discovered, by making a cut in my finger, that they also sucked human blood. Although I never saw that particular species do this in the wild, I later found that related species do indeed attack humans though even more rarely than they pester animals. However, in fact, I have only seen about 100 specimens in the wild in all my years of study. In those ‘early’ times, when Chiang Mai was much greener, a couple of times I came across a specimen which had ‘lost its way’ in my garden at the old Borneo compound where I used to live. Experiments in the lab required me to use myself as blood-bank for the moths so that I could study the piercing mechanisms thoroughly. It is actually somewhat painful, but you are so excited about it you really don’t care.”

While most of us lay folks, when we think about it at all, imagine that butterflies and moths flutter around sipping nectar and other sweet delights from aromatic flowers, Dr. Banziger reveals a darker side to these pretty flitters. Evolution has meant that the long soft proboscis used to suck nectar can, in some cases, strengthen and develop a piercing armature enabling it to penetrate fruits. Owing to the propensity of many moths to supplement their carbohydrate diet by drinking mammalian body fluids (tears, wound fluids, urine, etc.), Calyptra opportunistically turned to aggressively suck blood thanks to its fruit-piercing habits. Other moths did not evolve their proboscis but became experts in snatching tears surreptitiously from mammals, including occasionally man. They are not fruit-piercers and did not develop a piercing proboscis; this would hardly be welcome at such a sensitive organ as the eye. It is possible that eye and other diseases are transmitted this way and since these moths also attack humans, this finding has medical significance.

To date, and over years of intensive study and travel to places such as Laos, New Guinea, India and Nepal, Dr. Bänziger has discovered that 9 species of Calyptra, or vampire moth, to go by its macabre nickname, are blood suckers.

In all Bänziger, who has, for the past four decades, been affiliated with Chiang Mai University’s Entomology Department, spent over 20 years in the jungle researching his moths, with a few forays into other arenas in between, “I would normally spend five nights per week in the jungle during the few months a year when moths are plentiful,” said Bänziger. “I am not the only researcher of these species, but while most scientists have spent a few weeks on tear and blood sucking moths, I have spent two decades. I would often go to an elephant camp and follow the elephants and their mahouts into the mountains at night where I would wait for the moths to come. We would have to walk for hours and then return to sleep in a hut or, if too tired, just sleep there in the open in the forest, with the secret hope that my moths may present me with a visit to my eyes. I have also published about 20-30 articles aimed at scientists, doctors, vets, and other people interested in this area.”

“There are 17 species in the genus Calyptra, though, as mentioned, only 9 suck blood,” he explains further. “But there are over 100 tear sucking moths in the world, 50-60 in Thailand alone. It is all very fascinating, but after so many years, I decided that I would like to see the jungle by day time too, not just by night, so I have, for the past decade and a half, changed my field of study to pollination.”

While Dr. Bänziger will no longer have to brave the dangers of the night – which according to him are two-fold, mosquitoes and the rare human – he is far from taking the easy road.

“Orchids are very interesting flowers,” he continues with excitement. “There are over 15,000 species world wide but I was intrigued by lady slipper orchids, which are as rare as they are stunningly beautiful with only 70 species world wide.”

Being so rare and growing in very hard to access locations, the slipper orchid’s method of pollination had always eluded scientists. It turns out that tropical slipper orchids are pollinated by common hoverflies; but with near-glee Banziger explains that things are not quite what they seem with these dastardly orchids.

“The slipper orchids lure the hoverflies in with fake rewards, and by treachery, cause them to fall into their slipper-shaped pouch. Here they are kept prisoner until they can find the way out, sort of a tunnel ending in a narrow hole lined with pollen,” he explains. “As the hoverflies wiggle their ways out, the sticky pollen coats their backs, but there is no reward in sight for the hoverflies…except a good fright. Some species of lady slipper orchids are so treacherous as to ‘murder’ the progeny of their benefactors. The flowers emanate a scent imitating the odour of a colony of aphids (plant lice). These are the food of the hoverflies’ carnivorous young. So overpowering is this ‘love philtre’ (from the view point of the orchid which gets fertilised), but perverse an ‘infanticidal narcotic’ (from the view point of the hoverfly), that the hoverfly is misled to lay an egg. The hatchling will die by starvation. The aphids are fake. ”

It takes years to discover all this; years of Dr. Bänziger scouring the canopies of Chiang Mai’s forests for the elusive orchids. Once sighted, the 71 year old scientist draws his bow and arrow and shoots a rope up the tree, which he proceeds to climb. He regularly climbs trees 10-30 metres high and spends hours upon hours in close inspection of the hoverflies’ battles within the slipper orchids. “Unfortunately while you can hand-pollinate the orchids in a controlled environment, you can’t get the hoverflies to do it. I don’t take the orchids out of the wild though, I don’t collect, I study, I love them where they are,” he is quick to add.

Bänziger’s research may be sensationalised in this magazine, but he is a highly respected scientist whose sheer fascination with nature and passion for knowledge has led to a vast body of work. “Knowledge is important,” he says. “What I do today may be important to science in a hundred or two hundred years’ time. You never know. It is important to know how it all works so that if, for example, a species risks extinction, we may be able to save it.”

Dr. Bänziger married a Thai lady, who also works at Chiang Mai University, fifteen years ago and has infused his wife, Sangdao, with passion for his studies. The pair often go exploring and researching together and the fact that their home is 100 metres from the Suthep-Pui National Park, access is easy and frequent.

A modest man, Dr. Bänziger has led a modest life but one rich and bountiful in knowledge and scientific research. Dr. Bänziger’s name has already been given, by fellow scientists, to new species including a millipede, a fish, several moths, a beetle, an aphid and three liana vines, assuring his legacy.

“I am worried I won’t live long enough to publish everything, that is really my biggest worry,” says Bänziger. “I have two fantastic students who are passionate about their work, and I am no longer doing pilot studies, but there is not much funding anymore for field work, everyone wants to work in labs with modern equipment, so I worry about my students’ future. When I find something new I still write about it, for instance I discovered tear drinking bees in my garden a few years ago, fascinating! But I just want to consolidate all that I have studied and publish as much as possible. I am healthy, but at my age it can strike you any time.”