ภาษาไทยคลิกที่นี่

There are few greetings as charming as a “sawasdee jao” received with a gentle wai by a welcoming Lanna lady in her lilting kham muang.

For many visitors to Chiang Mai, this is the extent of their kham mueang vocabulary or knowledge of the language itself. In fact, there is a common misconception that kham mueang is merely a northern dialect of central Thai when in fact it’s a rich language with its own unique script and history, spoken by approximately six million people across the north of Thailand and Laos today. In spite of the great number of speakers, it is also a language under threat of extinction as fewer and fewer of the younger generation now speak it.

Kham mueang literally translates to ‘language of townspeople’; townspeople, or khon mueang, being what the Tai Yuan people of the north of Thailand call themselves.

Kham mueang is one of 95 languages in the Tai-Kadai family of tonal languages found in Southern China, Northeast India and South East Asia. There are over 100 million speakers of the Tai-Kradai family of languages spread across the region. But in spite of the vast number of speakers, Prof. Dr. Thanet Charoenmuang, of Chiang Mai University’s Faculty of Political Science and author of ‘When the Young Cannot Speak their Own Mother Tongue: Explaining a Legacy of Cultural Domination in Lan Na’, told Citylife, “[kham mueang] will be gone within 30-50 years, I guarantee. The destruction of the culture is very clear.”

The Birth of a Language

Let’s take a few giant leaps back in time for some historical context. The first great kingdom in the north of Thailand was Hariphunchai founded around 750 AD where Lamphun stands today. By then Buddhism had been introduced to the region for a few hundred years, brought over by traders from the South Indian continent. Pali was the language of Buddhist scriptures, and likely the first written language used in the area. The elite people of Hariphunchai were originally Mon, spoke Mon and wrote Mon. Over time, the script used for writing Pali and Mon were adapted to write the language of the newly emerging Tai elite and its people.

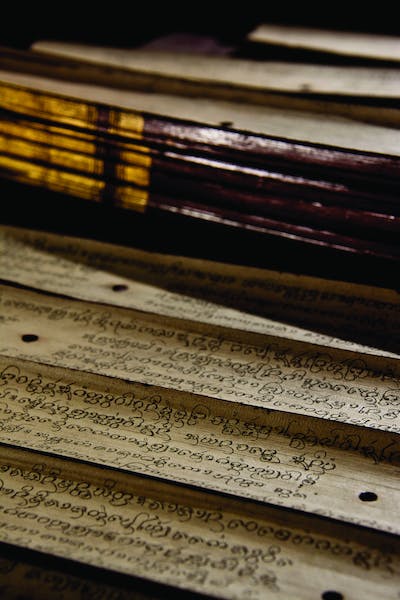

Lanna as we know it is a geographical construct, forged by the force of King Mengrai who founded the city over 700 years ago, and strengthened by his descendants who expanded its borders for the next 270 years. However, the ethnicity of the people were on the most part, Yuan and Mon. Once formed, the people of Lanna began to call themselves khon mueang and spoke kham mueang. It is speculated that King Mengrai would have wanted his own written language and adapted the Mon script into what is known as kham mueang today — evidence of this can be seen in the kham mueang script found on shards of pottery dating back to the decades following the foundation of Chiang Mai. The greatest era of Lanna saw the kingdom expand its borders south beyond Lampang, north to Yunnan and west deep into the Shan States of Burma. This was during the reign of King Tilokkarat in the second half of the 15th century, which saw Lanna and the newly emerging Ayutthaya fight a ferocious 30 year war, ending in Ayutthaya Kingdom temporarily moving its capital to Phitsanulok, defending it following Lanna’s successful capture and subsequent loss of the city. Until today Phitsanulok is known as Thailand’s barracks and Thai history books hardly ever mention the humiliating Ayutthaya-Lanna war. King Tilokkarat was also a deeply devout Buddhist and his reign (1441-1487) saw the golden age of Buddhism in Chiang Mai where temples were built and monks and pilgrims travelled far and wide to come study and copy dharma scripture from Buddhist palm leaf manuscripts, taking them back home to preach to their flock. Most of these manuscripts were written in kham mueang, thus spreading and strengthening the written language. The Lanna language was firmly established by this time and its written tradition was to remain strong until recent generations.

When Burma successfully annexed Lanna a century later, hundreds of thousands of men from the Lanna Kingdom were forced to join the Burmese in attacking and eventually successfully sacking Ayutthaya — twice over the next few hundred years.

“This bitter defeat by the Burmese, and their Lanna fighters, so enraged Ayutthaya that I speculate that Siam vowed never to allow Lanna to be independent again,” said Prof. Dr. Thanet. “Once arrogant in victory, the Burmese paid little attention to Lanna and over the course of the next few centuries the city became an empty shell, its citizens having dispersed to safer new homes during the constant battles. And so it was that a local chief in Lampang called Kawila was eventually able to join forces with Siam to expel the Burmese from Chiang Mai. We all exalt Kawila as the great leader (1782-1816) who brought Chiang Mai back from the Burmese, but the truth was he was put here as a puppet of Siam. Chiang Mai had been so deserted by that point that there were tigers and bears roaming the abandoned old city and Siam soon lost interest in such a poor vassal. Kawila, had autonomy in practice and proceeded to travel far and wide, bringing back thousands of Yuan people who had dispersed across the region over the past few hundred years of Burmese occupancy.” A new city was born, but this time born from a diaspora of Yuan people from across the region. Exactly five hundred years after King Mengrai founded Chiang Mai in 1296, Chao Kawila officially refounded the city in 1796.

We’re a Chatty Lot

Fortunately the Yuan people, as spread out as they were, shared a culture as well as the common family of languages and the little city was soon a bustling and busy town.

“Chiang Mai was a cultural crossroads, we were like a PTT Petrol Station between important pit-stops such as Moulmein in Burma, China’s Yunnan and the Siam cities closer to the gulf,” explained Vithi Panichphant, a leading Lanna scholar. “They all hacked their ways through the jungle to get here and rest, before continuing their journeys.”

“Mengrai built this city not for trade, but for service,” continued Vithi. “The main income wasn’t the buying and selling of goods, but in fact the collection of various servicing fees. You can see this in our character today. We are a chatty people. The first thing we say when we see a stranger is, ‘sawasdee jao’. It was always the women who did the greeting, as the men would often travel the trade routes working various caravans. Women were the real owners of the land; they didn’t leave the hearth and they knew everyone and everything.”

“Look at the sheer number of temples outside the old moat. If you go and knock on people’s doors in Chang Phueak and ask to peek at the back of their houses you’ll be shocked at how many pagoda remains are out there. These temples were the motels for the travelling caravans. Even when Chiang Mai was deserted for so many years and repopulated, they were still the same service-minded sticky rice culture people of old.”

Vithi recalls visiting Phuket twenty years ago with a group of students, all of whom were astounded to see that the great majority of reception staff at Phuket’s hotels were from Chiang Mai, “The Phuket people aren’t of a service culture, so they would sit at the back and it would be the Chiang Mai ladies greeting visitors. That is our culture, and our language is an integral part of it.”

Carving and Slicing Nations

So as Chiang Mai was quietly rebuilding itself far from Bangkok’s assessing eyes, the western nations began to eye our assets. “Suddenly the Chiang Mai rulers were making deals with British and French logging companies,” explained Prof. Dr. Thanet. “Bangkok, catching wind of this, began to salivate. They wanted a piece of the pie too. And that was when Bangkok forced Chiang Mai’s status to be changed from a tributary state to becoming a part of the nation of Siam in 1899.”

Thus began nearly a century of Siamese, then Thai, efforts to bring Lanna into the national fold, often through polemical means. “They called us Lanna Thai,” explained Prof. Dr. Thanet, “but there was never a Lanna Laos or Lanna Burma, we were just Lanna. They also banned our language. Even our most revered Kruba Srivichai who built the road up Doi Suthep was jailed five times, some for years, in Bangkok, in part because he continued to give sermons in kham mueang.” Schools were banned from teaching, and teachers from speaking kham mueang. Monks weren’t allowed to use it in prayer and instead forced to use the Thai script. “What were we supposed to do? We had been speaking kham mueang for centuries, you can’t just make us stop overnight. That is why the spoken language is still so ubiquitous, but just a few generations later the written language is now dead. We are all illiterate in our own language.”

The Compulsory Education Act of 1921, effectively banned all educational institutions across Thailand from using any language but central Thai, though the Siamese campaign to bring all of its far-flung regions into the central Bangkok fold had begun decades earlier under the reign of King Rama V.

In 1940, just over a year before the start of the war, Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram announced that, “All Thai citizens must praise, respect and believe in the Thai language and must feel honoured to be able to speak or use the Thai language.”

“With social mobility, modernisation and this loss of language, the Tai Yuan culture gradually disappeared,” said Nikhom Phrommathep, Senior Expert, Cultural Council Association of Thailand. “The less kham mueang we speak, the less Lanna we’ll become.”

Putting Things in Perspectives

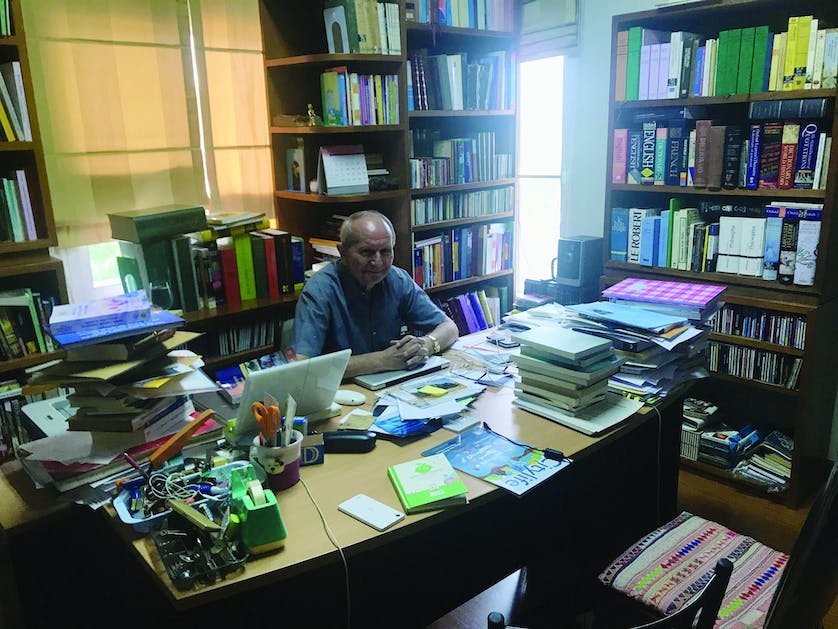

“Each year 25 languages disappear from the world,” said Dr. Louis Gabaude, Founding Director of the Library of the Chiang Mai Centre of Ecole Française d’Extrême-Orient. “Even here in Thailand, I have found there to be 65 languages, so when compared to the other 64, kham mueang is quite healthy. When you talk to some people, they will blame Rama V for Lanna’s cultural woes by imposing central Thai onto everyone. What people don’t talk about is central Thai monks used Khom script, a derivative of Khmer script, for Buddhist scripture. So when people in all regions were told to use central Thai script, central Thailand monks also had to use for Buddhist texts the script which was up to then used for vernacular or secular literature and needs. This reform wasn’t just imposed on the outer regions, but also on central Thailand itself. As an academic you can’t study history through modern regionalist eyes alone, you have to understand it within the context of its time. Rama V needed to unite a nation to resist colonialist western powers. He didn’t have the manpower to educate people in all 65 languages; that would’ve taken a thousand years. He wanted to build a nation which could compete with growing world powers and build up our collective knowledge and with that he needed uniformed standards to take to every district in the land.”

“You have to understand the mind-set of his time and not judge him by today’s standards,” he insisted. “Rama V’s and VI’s policies weren’t any different from what happened and still happens in almost all nations around the world. Generally speaking, elites including Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram, do not go out intending to destroy cultures just for the sake of destroying, they want to lead their nation forward and build it to be competitive. It is also too easy to critique and blame central governments alone. People are also complicit. Once so called ‘civilisation’ and ‘progress’ arrives, local people salivate and covet them to survive and climb the social ladder as high as possible, including regional academics!”

“In the olden days there were no nations as such,” continued Dr. Gabaude, “There were rulers and those living under them. People could pretty much speak, stand or shit as they wanted as long as they had allegiance to their ruler because they were ruled through might.”

“Things changed after the Second World War,” agreed Vithi. “It wasn’t just the Bangkok government pulling us into its orbit, the allies carved up the sticky rice Yuan people as they did most of the world. So suddenly, the sticky rice people were cut up into those living in Southern China, those in Burma got absorbed into the Shan State, Laos went to Laos and those in Vietnam became Vietnamese. And we became Thai.”

A Slow Death and an Attempted Rebirth

“It used to be that you went to Kad Luang Market and you would hear so many languages and dialects,” reminisced Vithi. “Now you can still pick up many accents, but they are noticeably fewer. What is very noticeable is that there are still many people speaking kham mueang, but as an accent, not as a language. Because we now share the written language with Bangkok, we are beginning to use its vocabulary as well. So many people today who say they speak kham mueang actually don’t, because they have no vocabulary, they simply put an accent onto Thai words,” continued Vithi.

“Like many parts of the world, our language shifted and changed from valley to mountain. Even streets! The people of Chang Moi say, ‘mua huan’ for ‘going home’ while those in Tha Pae say ‘pik baan’. It is these nuances which is disappearing completely.”

Many schools today are beginning to teach kham mueang again, a reborn pride in Lanna’s heritage having been resurrected over the past few decades. There are also many institutions teaching the language, with most students being monks studying scripture, doctors wishing to read about traditional medicine, academics or researchers looking to discover wisdoms and words of the past.

“Too little too late,” sighed Prof. Dr. Thanet. “Today you get a student at Chiang Mai University from Nan or Phrae and they will get teased for their funny kham muaeng because it’s not the same as Chiang Mai’s kham muaeng, so they will just skip it in its entirety and speak central Thai. The only people speaking kham muaeng now are the older generations, because the young don’t believe it has any value to them. Why should they bother? Movie stars don’t speak it, successful business people don’t speak it, their peers don’t speak it; it is seen as embarrassing and old fashioned.”

“All these academics wanting to revive the pride of Lanna, pride of kham muaeng, pride of culture,” said Dr. Gabaude. “Well, call me a skeptic. To revive a culture, the culture has to at least exist. There is hardly anything left to revive. Look at world trends, we are walking away from such pockets of culture. I wouldn’t like to place a bet on an alphabet holding more attention for the young generation than their iPhone.”

“I do find it sad though that the younger generations aren’t even calling themselves khon mueang anymore, they call themselves Thai,” added Prof. Dr. Thanet. “That happened really fast. “This so-called Lanna Renaissance is purely business, it has no basis on what is happening culturally, which is the opposite. A culture can’t be told what to wear or speak, but it has to simply do it as a daily habit, without thought or plan. It must just exist…and it doesn’t anymore.”