“A tattoo is more than a painting on skin, its meaning and reverberation cannot be comprehended without knowledge of history and mythology of its bearer. Thus is a true poetic creation and is always more than meets the eye.” – V. Vale and Andrea Juno, Modern Primitives.

During high school, I had my first inkling for an inking. For me, it was a rite of passage. It was the mid-90s in San Francisco, and it was to my parents’ dismay that I committed to this popular cultural initiation. Perhaps it was my obsession with all things esoteric – mythology, mysticism, cultural anthropology and Carl Jung – that prompted me to choose an ouroboros, an ancient symbol depicting a serpent or dragon eating its own tail. I was mesmerised by the hundreds of different historical representations of this symbol, along with the many mythical, alchemical, philosophical and psychological meanings. Hell, even Jung interpreted the ouroboros as having an archetypal significance to the human psyche. I found it all utterly fascinating.

Fast forward 15+ years. I am in Chiang Mai walking through the cluttered streets of the old city when I catch a glimpse of a man with several gorgeous images of Hindu deities Hanuman and Garuda etched into his skin, and a bold tiger leaping across his back. I take a closer look and compliment him. “I’m very grateful,” he says smiling. “This art has protected me during many fights.” He was a Muay Thai fighter.

This encounter led me to research all I could, pouring over books with images of people covered in sacred markings and drawings of animals such as tigers, dragons, birds and turtles. For me, it all mixed together into a colourful canvas celebrating and expressing the arcane and the spiritual.

To learn more, I spoke with Tom Vater, a 12-year Thailand resident and author of a book on tattoos called Sacred Skin.

“I wrote Sacred Skin because it’s a niche subject that really gets to the heart of Thai culture and the social economics here,” he told me. “It is an art for Thais and by Thais that goes beyond the growing modernisation of skyscrapers, beaches and soap operas. Sak yant isn’t going anywhere; 15-20 percent of Thai people have a sak yant tattoo and there has been a renaissance of this art in the last 10 years.”

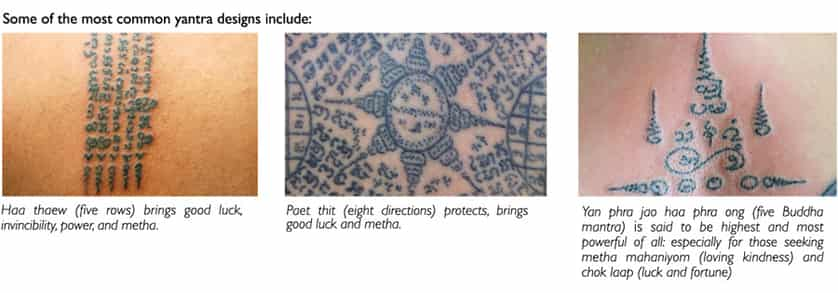

Influenced by a mix of spiritual traditions including Hinduism, Buddhism and animism, sak yant has been used for centuries to offer protection from accidents and to bring metha (loving kindness), courage, good fortune, health and prosperity to the wearer. For Thais, this art is a spiritual path.

Of course, many people who get tattoos today are not doing so for spiritual reasons. They aren’t interested in researching the significance or adhering to ancient traditions. For some, body art is just a fashion statement, or the dreadful results of a rash (and potentially inebriated) impulse. Just Google “tattoo fail” and hilarity (or shock) ensues.

“People today don’t often want a sak yant because the tradition is actually to follow the five Buddhist precepts afterwards in order to keep the tattoo powerful – refraining from killing, stealing, lying, sexual misconduct and intoxication,” says Chris Kamhoms, a non-sacred tattoo artist and owner of the popular Chiang Mai studio, Skinart. “Most people are not willing to have those restrictions.”

Sak yant is not like any ordinary tattoo. The application involves either a long metal rod or bamboo stick, which is used to insert the ink deep into the skin through a process called ink tapping. The ink (usually a clay mixture) is infused with various herbs, such as antiseptic waan root, wild ginger, sesame oil, and, according to travel writer Joe a woman who died in pregnancy in a graveyard temple in the middle of the night. How nice. Apparently this adds power to the ink.

“A man without tattoos is invisible to the gods.” – Iban proverb in Borneo

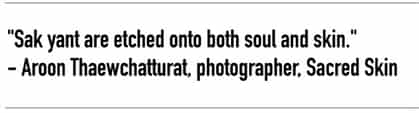

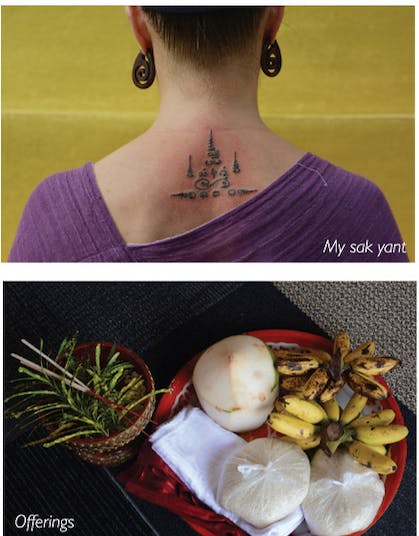

All this research into sacred tattoos made me feel that same old itch I had in high school: the desire for another tattoo. This time, I wanted a sacred sak yant. And that’s how I came to find myself here, kneeling inside a small Buddhist temple in Doi Saket called Wat San Makieng. In front of me sits a gold phan (raised tray) of highly specific offerings that I was instructed to bring: a fresh coconut, two bunches of bananas, two bags of rice, red and white cloth, flowers and an envelope filled with 370 baht. A large golden Buddha towers majestically above me while a young monk, Phra Ajarn Thecharangsi, observes, seated in the lotus position so motionless, he appears to be a statue himself. I gingerly set my offerings before him, wai and then bow three times to the floor. As I close my eyes, the scent of sandalwood dances around me.

“You know, everyone is important,” says Phra Ajarn Thecharangsi. “For every individual I have tattooed, it has been a memorable experience and honour for me.” The monk asks what I am seeking (i.e. protection, luck, love, compassion, etc.) and then begins sketching swirling Sanskrit characters in a triangular formation on a notepad. Traditionally, the monk selects the design and placement by reading the client’s energy and needs.

According to Phra Ajarn Thecharangsi, the imagery hasn’t changed much since ancient times, but many of the designs of today are more detailed due to increased skill in this art. The design he creates for me represents Bodhisattvas that have reached Nirvana (the swirl in the middle) and the top of the design represents the coming Buddha, yet to be incarnated. The design incorporates the four elements of Earth, Air, Fire and Water. The script and blessing offers a mix of protection, luck, metha, compassion, strength, and stillness of mind. A pretty feel-good combination if you ask me!

He escorts me to another room filled with dozens of Buddhist statues. My mind is teeming with questions: Will the needle hurt? Will this magic mark and incantations change my life? I close my eyes and wait nervously for the first prick and then it begins. A soothing tingle fills my entire body, beginning from the back of my neck.

Tap, tap, tap…

A few minutes later, on the brink of a hypnotic trance, my brain and body melt into a balmy, opiate-like bliss. I’m pretty sure I could sit here all day and have him tattoo my entire back. I don’t want it to end, but unfortunately the tattoo takes only about 30 minutes to complete. Then the monk begins to chant rhythmic incantations, prayers, and blessings – I feel a cool puff of air on my sak yant and I have chills. I wait until the moment permeates my entire being, then slowly turn, bow, thank him and head back into the sunlight. I float back to my guesthouse in a daze, light incense, and reflect on the beauty of the experience.

My personal encounter leaves me wondering about the future of sak yant. Will the traditions last? Will they retain their sacredness? Or are they doomed to surrender to tourism and lose their meaning entirely?

“Sak yant won’t go away simply because it is a deeply held expression and moral reminder to stay on the right path,” says Tom Vater, reassuringly. “Thai people are still religious and sak yant masters in Thailand are like spiritual mentors or counsellors in the West. Thais will continue to get sak yant. Foreigners get sak yant for various reasons – some will take the time to research the history, art, magic, significance and spirituality behind it, but there will always be the farang that just think it’s fashionable.”

What does all of this mean in the context of my own journey? It’s simple really; I believe in the beauty and art of the sak yant. For me, the inspiration, myth, magic and meaning won’t fade anytime soon.

Related Articles

Tattoos in Honour of His Majesty