In 2010, a Thai woman named Piyawan Palasarn drugged a two-month-old tiger cub and packed it into a suitcase. She piled in stuffed toy tigers alongside it, as though they would prevent airport security from detecting the real, live, endangered animal she was illegally trying to smuggle out of Thailand in her carry-on luggage.

Piyawan was caught by authorities at Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi Airport and, per usual, released on bail. The international press reacted with a slew of pun-laden headlines about the cat being out of the bag and a new entry into the stupidest smuggler’s hall of fame, and the world quickly moved on to the next sensational news story. But the incident highlighted much more than just one woman’s lack of common sense.

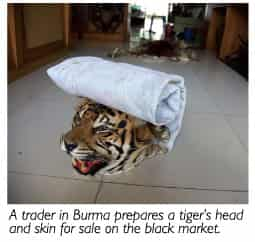

In 2013 alone, Suvarnabhumi officials have intercepted over 1,000 animals being illegally trafficked via passenger planes. Just last month, an unaccompanied bag from Bangladesh was found to contain 470 endangered tortoises. Earlier in the year, a few cases declared “fresh fruit” turned out to be 2,000 rat snakes and cobras. The stories are endless and absurd, but they all point back to one scary fact: illegal wildlife trade is on the rise, and Thailand is the world’s biggest hub.

Of course, as is the case with most black market dealings, small-time traders like Piyawan are just the tip of the iceberg, leading back to much more powerful entities. Frustratingly, many of these big-time traders are actually known to the government and other anti-trafficking authorities, but continue their dirty business unhindered thanks to a lack of resources, corruption and general apathy. Add to the thousand animals confiscated at Suvarabhumi the thousands that never get intercepted, through myriad airports and border crossings all over Asia, and you will begin to formulate a chilling picture of just how large this multi-billion dollar issue really is.

A Walk on the Wild Side

It’s a rainy day in Chiang Dao as we make our way over narrow, rutted roads of slick mud, past fertile farmscapes and hidden forest temples. The rains beat down in their last hurrah before the dry season, but the beauty of the Chiang Dao mountains cannot be missed, even soaked in deluge and clouded by mist. We’ve been driving awhile, and I’m starting to wonder if we took a wrong turn when suddenly we see a large black bear with a white chevron-shaped patch on her chest frolicking in a puddle, her bamboo jungle gym domain enclosed by a wire mesh fence. We’ve reached our destination.

The Wildlife1 Sanctuary, built on 15 rai of verdant river valley, is flanked by over a thousand square kilometres of protected national park land. It is a vision-in-progress for Adam Oswell, an Australian photojournalist and conservationist who has been living and working in Thailand for over two decades.

While Wildlife1 – a registered NGO that aims to increase conservation and fight back against illegal wildlife trade – has been around for four years, it wasn’t until early 2013 that Oswell’s biggest vision began to take form.

UPDATE: The sanctuary has been out of operation since 2014 so please do not contact them upon request.

“I’m not a scientist,” says Oswell. “But honestly, there’s not enough time for science. With the current rates of trade and extraction, the only relevant thing that’s going to save animals is protecting them. It’s as simple as that.”

Over the past year, Oswell, his partner Pim, his sole full-time employee Wongsakorn “Yu” Duangpayap and a number of short-term volunteers have been working ceaselessly to build what is now a fully-functioning conservation facility in Chiang Dao. Today, Wildlife1 houses four monkeys, three moon bears and two slow lorises – all rescued from the illegal wildlife trade (along with three former street dogs named DJ, Ruby and Curtis). The sanctuary is completely off the grid thanks to a mere one-kilowatt system of solar panels, and ripe with fruit trees and an organic herb and vegetable garden that Oswell hopes will eventually become the sole source of food for both people and animals living onsite.

The ultimate goal is to create a completely self-sustaining model (the likes of which have never been seen before in Asia) for wildlife protection and rehabilitation, with a veterinary clinic and training centre onsite, larger open-plan animal enclosures, more housing for volunteers, and even infra-red unmanned camera technology to monitor the protected area. So far, most of Wildlife1’s funding has come out of Oswell’s own pocket, along with some support from Hauser Bears in the UK, Elephant Nature Park and the International Student Volunteer programme. But in order to create a viable income stream, more start-up funds are desperately needed.

“It’s a big vision but I have high hopes,” says Oswell. “This land has everything – running water, fertile soil, and a good habitat for the animals we rescue.” The area also holds its fair share of international history and local lore. In the 1930s, the first-ever audio recordings of wild white-handed gibbons were captured here, and locals say that the land is inhabited by a powerful tiger spirit.

Tigers Wanted

You could say that most of Asia is inhabited by tiger spirits. While tigers used to roam throughout Thailand, today there are an estimated 250 left in the wild. Globally, according to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), their numbers are currently at an all-time low, with 97 percent of the tiger population lost over the past century. Thailand is one of the rare places where wild tigers can still be found, in places like Thung Yai and Huai Kha Kaeng National Parks, but even those living in protected areas are under direct attack from poachers.

The tiger cub rescued from the suitcase in Bangkok was sent to a Department of National Parks (DNP) wildlife rescue centre in Ratchaburi. But unfortunately, that doesn’t mean happily ever after. Thailand’s DNP facilities are overcrowded and under-resourced, lacking the capacity to deal with the sheer number of animals confiscated from illegal traders. And yet this is probably where the tiger will spend the rest of his days. According to Oswell, there has never been a successful reintroduction of tigers back into the wild after living in captivity. Never. Not one.

“If you set a tiger free in the wild after it has had the slightest human influence, it is virtually guaranteed to either die or attack a village, because it has already been conditioned toward humans,” says Oswell, who adds that an insurmountable degree of habitat loss ensures that there’s no longer any place where a reintroduced tiger could be far enough away from humans to stay safe.

“The world isn’t big enough for tigers anymore,” he says.

Bitter Medicine

Oswell’s conservation work does not stem from radicalism. Indeed, he is surprisingly calm and soft-spoken, even when discussing difficult subjects. He is not a vegetarian and has no problem with traditional game hunting; rather, it’s the modern influences of industrial farming and profit-driven killing and poaching that fuel his desire for change.

“In my years travelling around Asia as a photojournalist, I began to notice huge volumes of wildlife trade,” recalls Oswell. “In the mid-80s, Asia was very biodiverse. Over the years, I watched how quickly rapid development was raping the land. By the late 90s, so much was gone. It all happened so fast.”

Indeed, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation, tropical Asia’s annual deforestation rate between 1980 and 1990 was a chart-topping 9.6 million acres per year. Today, nearly all of Thailand’s lowland forest has been cleared, with only a few protected national parks left. But just as deforestation directly contributes to a decline in wildlife, so does wildlife decline affect the earth, and all who live on it.

“Wildlife trade is now so large it could have irrevocable consequences for life on our planet,” explains the Wildlife1 website. “More and more species now stand at the verge of extinction. The disappearance of keystone species disrupts critical food chains, which in turn affects the balance of nature.”

As the human population increases, the wildlife population continues to decline. Thousands of species (the WWF estimates at least 10,000) are now going extinct every year. Some of the most endangered and magnificent creatures of all – such as tigers and elephants, who are traditionally revered in Asian culture – are being poached and slaughtered to feed a booming yet completely unnecessary demand.

The three biggest reasons behind all this wildlife traffic? Traditional medicine, exotic pets and exotic meats.

It could be said that traditional medicine is one of the most destructive hoaxes to ever befall a region. Bogus claims which have long been disproved by science continue to fuel the desire for exotic animal parts – tiger penis, bear bile and monkey brain, to name just a few – which in fact do absolutely nothing for those who spend thousands to ingest them.

“It’s a status thing,” says Oswell. “Ninety percent of the people surveyed in Vietnam who are buying illegal rhino horn are doing it to give to their employers to gain favour. People are even snorting crushed up rhino horn now. It’s more expensive than cocaine and it does nothing at all.”

Horror Stories

At the Wildlife1 sanctuary, there are two adorable moon bear cubs named Samson and Lila. When the DNP found them in a small village on the Burmese border (and eventually handed them over to Oswell to raise at the sanctuary – an encouraging show of faith in his work), the villagers told authorities that they had found them in the forest and their mother had abandoned them.

“Of course, this is a lie,” says Oswell. “They killed the mother and their plan was to raise the cubs and sell them on the black market. Bear paw, gallbladder and bile are highly regarded in traditional Chinese medicine, even though they have absolutely no medicinal value.”

Little Lila, who looks like a teddy bear come to life, is currently eating wild berries out of the palm of my hand, her other arm wrapped around my waist in a real-life bear hug that I thought could only happen in my dreams. As I watch her, more than a little smitten, I wonder how anyone could ever harm a creature like this. How did we get to this point, as a civilisation: our forests reduced to concrete deserts, our animals a collection of useless body parts?

Oswell’s horror stories are endless, and he says he can’t even tell me the worst ones. He describes a casino near the Thai-Lao border where dozens of endangered animals (including leopards, tigers, bears and monkeys) wait in tiny cages for gamblers to come out and purchase them to be slaughtered on the spot for an expensive winner’s dinner. It’s still open, but there’s little Oswell can do to intervene – buying the tortured animals only fuels trade and lines the pockets of their captors, and local authorities refuse to step in.

Just a few years ago, there was a report from a restaurant in Bangkok that catered exclusively to Korean and Chinese tourists, where bears would be lowered in cages paws first and grilled alive because the fear-induced rush of adrenaline was said to make their meat tender. Luckily, that place was shut down after a Korean tourist finally reported it to local media, but Oswell said the only thing recovered from the site was dead bears.

“The fundamental issue is that people have no respect for lives other than their own,” says Oswell. “Modern society has become so removed from nature that we’ve lost sight of our vital connection to it.”

A Second Chance

Time spent at the Wildlife1 Sanctuary in Chiang Dao is a welcome reminder that despite all we’ve lost, there is still some human empathy left in the world. As we amble around the premises with crates of locally grown produce, helping Yu feed the monkeys their breakfast (Jack gets eight slices of pumpkin, two bananas, and one egg yolk; Nong Dao gets six pumpkin slices, one and half bananas and the whites from Jack’s egg), I ask Yu which animal is his favourite. He pauses for a second, before breaking into a smile. “All of them!”

Meanwhile, Canadian volunteers Tom and Taj are hard at work helping Oswell construct a new outdoor bear enclosure, which could be finished as early as this week. It will be an extension to the cubs’ current compound, and eventually Chabaa, the adult moon bear, will join them. Oswell says that pairing the young orphaned bears with an older female will be good for all parties involved. He has been slowly introducing the cubs to Chabaa by allowing them to sniff at each other through the mesh fence, and the interactions look promising (and adorable).

Like the tiger in the suitcase, Lila and Samson will never be ready for reintroduction into the wild. Their chance of that was lost the moment their mother was killed and their infancy was reduced to a cage. A bear orphaned and reared in captivity at such a young age has little to no chance of survival in the wild. But as we take them out for the first of three daily romps around the property and watch them delicately paw the forest floor for termites, wrestle with each other, and shimmy up tree trunks (where they commence wrestling in an impressive show of multi-tasking), it’s clear that all is not completely lost. These little bears have regained at least some of what they were rightfully owed all along – a chance at a peaceful life.

Website: www.wildlife1.org

UPDATE: The sanctuary has been out of operation since 2014 so please do not contact them upon request.