Thailand, we have a problem. The most recent UN Trafficking in Persons Report is quite long and very dry, but its message is clear: human trafficking is a huge issue in Thailand, and not enough is being done to stop it.

For anyone even slightly familiar with the culture of human trafficking in Southeast Asia, this statement rings true. Traffickers run rampant and though the government has instituted legislation to deal with them (most notably the 2008 Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act), conviction rates are shockingly low: of the 305 trafficking-related cases brought to court in 2012, the government convicted only 10 offenders. This hardly registers as a blip on the vitals of progress and implies that little attention is being given to the migrants and Thai nationals being sold into forced labour across the country every day.

So, if little is being done at the national level to combat these issues, what is being done at the local level? A simple Google search of “Human Trafficking Chiang Mai” reaps pages and pages of links to various anti-human trafficking organisations. They’ve got hordes of volunteers and write prolifically about the “good” work they’re doing. Their pages are plastered with photographs of survivors baking cookies or taking English classes or smiling with large, toothy grins. I’ve got nothing against photos of cute kiddos or heartfelt blog posts about rescuing survivors from bad situations or even a page dedicated to asking viewers in the west to funnel donations toward the cause. However, the deeper one dives into this cyber pit of NGO blogs and websites, the easier it is to feel like all of this is simply promotional material for the organisations themselves, rather than useful resources on the actual issue of human trafficking. And, given that a large chunk of these organisations are faith-based, it seems too that many are clouded with religious jargon that subtly intertwines Jesus, the light and the way with stories of survivors, statistics and mission statements until the issue of human trafficking is hardly discernible from the issue of faith.

A phone conversation with David Mathieson, Senior Researcher in the Asia Division of Human Rights Watch, seems to affirm my most cynical beliefs on the effectiveness of the modern NGO. “NGOs involve a lot of pretence, a lot of patting themselves on the back,” he says. “Instead of focusing on the deep-rooted issues, many of these groups focus on small episodic victories that might appeal to someone viewing their website abroad, but don’t really solve the problem.”

He continues, “Organisations must listen to the community directly suffering. They must listen to the strategies already in place by community leaders and they must listen to those being trafficked. Otherwise, their strategy as an NGO is flawed.”

When we speak of human trafficking, then, it is crucial to focus not solely on the issue, which is often written about with sensationalist vigour that does little justice to survivors, but to also give critical focus to the organisations that claim to be working toward combating human trafficking. But it is not about pointing fingers and declaring groups “good” or “bad.” Rather, it is about training a thoughtful lens on the landscape of human trafficking volunteer work in Chiang Mai, to reach out a hand and ask “What can we do better?” and “How can we work together?”

Defining the Issue

One of the biggest challenges in crafting policy or legislation about human trafficking is deciding what constitutes “trafficking” and what does not constitute “trafficking.” A popular opinion seems to be that most people “know it when they see it,” referring to the idea that most individuals, regardless of how informed or uninformed they might be, would be able to recognise a “victim” if they saw one.

Though this might work in the case of a female underage prostitute, the global poster child for illegal sex work awareness, what about the smiley children selling flowers on the street or challenging tourists to arm-wrestling matches as they sit at cafés? What about a “wage-earning” factory worker or the beggar sleeping outside 7-Eleven or the old woman wearing “traditional” tribal clothing selling bracelets and wooden frogs with sticks? Are these individuals trafficked? How would you know?

The point is, you probably don’t know, which is why a concise definition, though imperfect, helps us to better understand the issue. So let’s establish one. According to UN Trafficking Protocol, human trafficking is defined as “the recruitment, transport, transfer, harbouring or receipt of a person by such means as threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud or deception for the purpose of exploitation.” This is particularly helpful because it divides trafficking into its three major components and acknowledges the breadth of the issue, which involves a lot more than just sex work or sexual exploitation.

On the other side, any discussion about “effectiveness” or what groups should do to be more “effective” is tricky, difficult and, honestly, inherently flawed, but for the sake of this piece, I believe it useful to have a guideline. According to the UNESCO report “Combating Trafficking in South-East Asia: A Review of Policy and Programme Responses,” all anti-human trafficking organisations should include: 1) capacity-building activities, like improving legislation and skills training, 2) awareness raising and advocacy to promote positive attitudes for policymakers, the public and communities at risk and 3) direct action, like interventions and alternative livelihood strategies.

These are the aspects we can focus on when we try to examine individual anti-human trafficking organisations in our community, keeping in mind these crucial questions: Are organisations working to establish capacity-building activities for survivors? Is participatory community development being encouraged? Are community members directly involved in the organisations? Who has the power in these organisations and whom does the mission benefit most?

In Focus

In Chiang Mai, and the North in general, one cannot speak about human trafficking without speaking about FOCUS (Foundation of Child Understanding, formally TRAFCORD), an organisation that, since its inception in 2002, has been doing highly effective work to combat human trafficking.

In a conversation with FOCUS manager and programme coordinator Phensiri Pansiri, much of what she says echoes the sentiments expressed in the UNESCO report. “Success is how you define it,” Phensiri tells me. “For us, success comes in being able to establish community centres throughout the North, where community leaders teach prevention and vigilance to their neighbours. It comes through working directly with the government to rescue and rehabilitate survivors. It comes through vocational training and constant communication between other organisations and affected individuals.”

Their approach, as Phensiri describes it, revolves around a “G to G” or “government to government” strategy.

“We are constantly in communication with the governments of Myanmar and Laos, with China and Vietnam, all the countries in the Mekong Region,” she explains. “Because of Thailand’s location, we are not just dealing with Thai nationals being trafficked, but foreigners from several different countries. Our goal is to stay aware of what is going on throughout the region. Though our office is in Chiang Mai and our direct attention is on the nine Northern provinces, we cannot ignore what is going on elsewhere.”

When I ask her about governmental corruption and whether or not this presents a problem in the work she does, Phensiri says, “Yes, there is corruption. There is corruption everywhere, but the work we want to do we cannot do alone. We are only nine staff and the government is instrumental in helping us to do rescue work on a large scale.”

Toward the end of our interview, I ask Phensiri whether or not she feels like the landscape of human trafficking has changed much in the 12 years since FOCUS’s founding. “Unfortunately, no,” she replies. “In fact, the problem seems to be growing bigger…but I know that good work is being done and that’s what is important.”

As a final question, I ask her about the community of volunteers working in Chiang Mai, specifically about whether or not she perceives there to be a difference in effectiveness between faith-based versus non-faith based volunteers or short-term versus long-term volunteers. She pauses for a moment and responds, “No, not really. It doesn’t matter if you come here for three weeks or three years or if you come here because of Jesus; if you are thoughtful and intentional with the work you are doing, it is good work. That is what matters, that we are here and responsive to the needs of those affected.”

One Life at a Time

Children’s Organisation of Southeast Asia (COSA) is a non-profit organisation dedicated to the prevention of human trafficking and exploitation. The main feature of the organisation is a large housing compound where 50 at-risk hill tribe girls live. The approach of the organisation, as founder and president Mickey Choothesa tells me, is an “upstream” one that focuses on educating local communities about the realities and dangers of trafficking.

“The reality is that the culture of human trafficking is so deeply embedded in Thai society that no one questions it,” he says. “It is a way of life, but it doesn’t have to be, and that is what we share with these communities.”

This focus on education extends to the 50 girls who live at COSA house. Though the girls live at the home and receive weekly English lessons from the volunteer staff, they are fully integrated into public schools in Mae Rim and Mae Taeng and are provided with the necessary support (monetary as well as emotional) to not only complete high school, a luxury otherwise unavailable, but to excel at a university level as well. The environment Mickey and his staff have created is one of hard work and dedication; consequently, the girls at COSA are consistently the highest performing students at their schools.

“Young girls are overlooked in Thai society,” says Mickey. “They are the ones who leave school first, the ones who don’t continue to receive an education. This lack of education and awareness puts them at risk of being trafficked. We help to ensure that they have accessibility to good schools, so they can finish high school and go to university.”

Mickey says that in just two years time, they’ll be expanding housing to hold up to 100 girls. He acknowledges this as a success, but also acknowledges that it is not as significant as people might think: “For every one girl I’m able to rehabilitate, 10 other girls slip through my fingers.”

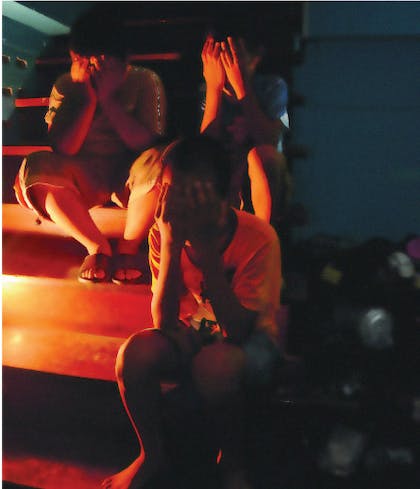

Of course, this issue of inadequacy is one that all NGOs face, a constant struggle: we cannot help everyone. Some take comfort in the notion that a difference can be made on a small scale; one life made better makes it all worth it, right? But another issue facing NGOs here in Northern Thailand is the lack of communication between them, which can be even more insurmountable when physical distance comes into play.

“It’s difficult to talk about other organisations, because we’re pretty isolated down here. That’s probably one of our biggest challenges. We want to network with other organisations and share the resources we have, but we’re far from the city,” Alexa Pham tells me. Her organisation, Daughters Rising, works to prevent human trafficking by empowering at-risk girls through education and community development. Chai Lai Orchid, her newest venture, takes these principles of empowerment and education and directly applies them to the real life running of an eco-resort located in Mae Wang, about an hour from Chiang Mai. The eight at-risk girls who live at the resort receive safe shelter, yes, but they also have to go through a six-month programme of intense hospitality training.

“The girls do everything: they clean, they cook, they interact with guests. Prevention is about building up a skill set as much as it is about anything else. In the six months they’re here, they learn things they can apply to future work in other resorts,” Pham explains.

Though these skills are tangible, Kayla Gill, Daughters Rising’s volunteer programme coordinator, says that it’s difficult to gauge success. “The girls here think positively of themselves. They have dreams. But those aren’t statistics or things you can hold onto. Because of this, it’s hard to talk about ‘effectiveness.'”

Going with God

In the case of anti-human trafficking work, which Christian groups in particular have flocked to in droves, one has to wonder what, if any, space Jesus should be given in discussions of prevention and rehabilitation. When there are so many factors to consider in working with those trafficked or at risk of being trafficked (socioeconomic concerns, mental stability, physical health, documentation, labour rights, community reintegration), why focus on religion at all?

Faith as a motivating factor for volunteer service is understandable, but it is not something that survivors desperately need. Though spiritual connection might elevate the mental state of an individual, Jesus cannot directly provide housing, job training or an end to systematic oppression, so can faith really bring about tangible change?

I sit with Liz Olsen, a programme coordinator for faith-based anti-trafficking organisation Lighthouse in Action. We’re at a table near a window at Zion Café, a business run by the organisation. In the centre of the café is a large, iron spiral staircase. During the course of our conversation, dozens of perky young white people descend and ascend the staircase. They wear athletic clothing and speak with American accents. Liz tells me they are the volunteer teams and that they live above the café, which holds room for 126 volunteers at a time. She refers to them as “teams” because most of the volunteers don’t come alone, rather coming as parts of large mission or church groups, most of which stay for around three to four weeks.

Liz refers to their work as “bar ministry,” where teams of volunteers go out into the red-light district to meet and get to know girls working in bars. They’ll go to the same bars for a few nights until they establish relationships with the girls, after which point they invite them back to Zion Café for English classes, karaoke parties and movie nights.

“I tell my volunteers not to preach Jesus in the bars, but to just be friendly and get to know the girls and invite them to Zion. We want them to know that they are valuable and beautiful and that’s the main goal.” When I ask her about whether her volunteers receive special training before going out into the bars, she responds, “They receive three days of training before going out to do their work, in which we talk about Thai customs and what good bar ministry is.”

When I press her about preventative measures, she tells me that they “work with the girls on a one-on-one basis. We ask them what their dreams are, what they want to do with their lives. If they want to open up a handicraft store, we help to give them the skills to make handicrafts and run a business. If they want to work in a café, we’ll hire them here at Zion.”

For most of our conversation we’ve yet to touch on the topic of Christianity, which I bring up only near the end when I ask her how important the ministry is to the overall mission, “We believe that true transformation comes through Jesus Christ,” Liz replies. “We don’t pressure the girls, but yes, we do believe that true transformation comes through Jesus.”

Another Angle

Founded by missionaries 27 years ago, New Life Center is one of the longest running anti-human trafficking organisations in the city. It has been recognised for its work on a national and international level, according to the centre’s social worker, Wandee Cheunchooprai, who agreed to speak with me along with one of her full-time volunteers, Melissa Northrup.

Although New Life Center is a Christian organisation, Wandee notes that ministry is just one part of the picture. “Here at New Life Center, we teach classes on Jesus and the Bible, but that is not the sole focus of our organisation,” she says. “We provide education, vocational training, counselling, shelter, health care, handicraft and income generation as well as prevention work in affected communities. That our girls [the organisation works with at-risk girls in the Mekong region] feel safe and respected here, regardless of faith or education or anything, is the most important thing.”

When I ask Wandee about the importance of networking and collaboration in the community of volunteer organisations in Chiang Mai, she further elaborates: “Regardless of faith or non-faith, we have to work together and be in constant communication with one another.” She speaks profusely to the value of the strong network the organisation has been able to establish with a variety of groups, namely: Mekong Consortium on Safe Migration, TRAFCORD/FOCUS, United Nations Inter-Agency-Project to Combat Trafficking in the Mekong Sub-Region and the Upland Holistic Development Programme.

Melissa speaks up at this point, stating, “To see all these groups collaborate with one another is something really special. Each group has their expertise and when they work together, that’s when they’re most effective.”

As we wind down into the last few minutes of the interview, I ask Wandee about what someone should keep in mind when thinking about starting an anti-human trafficking organisation in the North. “I think the person would have to know about Thailand and Thai people,” she says. “You have to learn from them, not just teach them. There are many organisations here filling in many holes [in the system], you should only start a new organisation if you feel there is a specific hole that another organisation is not filling. If we all put all of our energy filling in one hole, hundreds of other holes go completely ignored.”

When looking to the future, the number one goal of Melissa, Wandee and current Director Karen Smith is to install a member from an affected hill tribe community as director of the programme. Community members make up a slight majority of staff at present, a fact that Melissa and Wandee agree helps to make the organisation such a success.

Looking Forward

Though this article only takes a quick look at five organisations (a very, very small sample of the much larger community of volunteer organisations here in Chiang Mai), it is clear that the establishment of strong networks, community-based education and development, direct vocational training as well as empowerment of affected community members through positions of power and influence in leadership structures are characteristics of some of the most successful anti-human trafficking organisations in Chiang Mai. In regards to faith, its incorporation into an organisation is not necessarily problematic, but if ministry is the main thrust, its affects seem to be superficial.

Further, retaining a tight focus on the actual deep-rooted issue of trafficking must be at the core of a successful organisation. Honorary British Consul Ben Svasti, whose work with TRAFCORD (a.k.a. FOCUS) and human trafficking in general spans 15 years, speaks to this. “It’s easy to get lost in the drama of rescue raids and the scandal of underage sex work as opposed to focusing on prevention and education at a community level, which are the only things that can change the system,” he says.

Mickey Choothesa of COSA shares similar thoughts: “Once an NGO becomes successful and recognised, they start going in for fancier offices and bigger donors and they lose sight of why they started working in the first place. If you take your eye off the issue of human trafficking, for even one moment, you’re lost.”

Micky glances around the beautiful green grounds of the COSA house and continues. “In a perfect world, we wouldn’t have to exist at all. We could wrap up and leave because communities would be able to sustain themselves. But until then, we do the work we can and try to make as much of an impact as we can. No group is perfect, but I believe the community of volunteers organisations in Chiang Mai is strong and, for the most part, doing good and beneficial work.”