One of the most negative aspects to develop out of the newly democratic and open society of Burma is the use of freedom of expression and freedom to gather as a catalyst for ethnic and religious hate mongering.

While ethnic tensions between the Buddhists in Rakhine state and their Muslim Rohingyan neighbours have been underlying for generations in both civil society as well as politically, the new open society has allowed for these tensions to be provoked into riots, violence and the destruction of Rohingyan villages in and around the capital of Rakhine state, Sittwe. This has led to a mass exodus of hundreds of thousands of Rohingya to Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camps in outlying areas.

The Burmese government has done little to quell the violence or to set up proper support structures within the camps, where conditions are extremely poor with little access to clean water and enough food as well. The Rohingya that have stayed in Sittwe are relegated to a cordoned-off neighbourhood called Aung Mingalar that is also referred to as “the ghetto.” It is controlled by state security forces that do not let the Rohingyans leave, making it nearly impossible for them to take part in any kind of commerce. These photos depict the day-to-day existence of Rohingya living in Sittwe. While the violence towards Muslims began here, it is now spreading nationwide, spurning a fear of Buddhist jihad as well as retribution by both domestic and foreign Muslims.

Captions:

01. Rohingyan men pray in a temporary mosque at an IDP camp outside of Sittwe. One of the first established IDP camps outside of Sittwe. Each longhouse houses about 10 families.

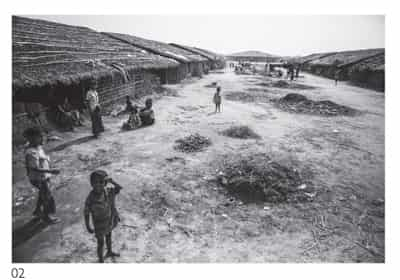

02. Rohingyan women amongst their temporary homes. Many of those seeking refuge do not gain access to official aid from the government or NGOs.

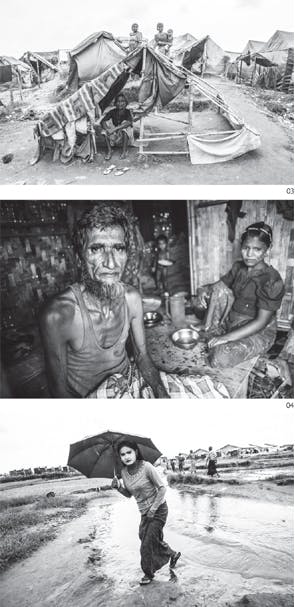

03. A Rohingyan couple eat on the floor of their temporary shelter.

04. A Rohingyan woman crosses a flooded area of an IDP camp outside of Sittwe.

05. A Rohingyan man cleanses himself before prayers at an IDP camp outside of Sittwe.

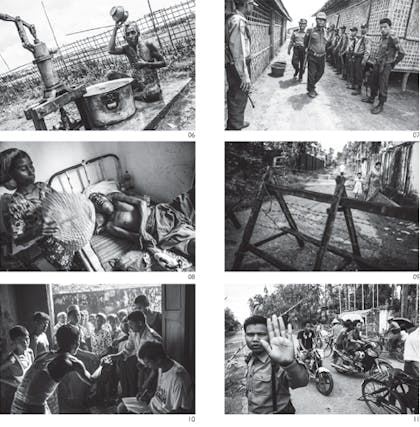

06. A Rakhine police patrol runs a drill in a Rohingyan IDP camp. Tensions are high between the security forces and those living in the camps.

07. A Rohingyan man shot by Rakhine police writhes in pain as his wife fans him while waiting for medical attention at an underserviced clinic in the Rohingyan IDP camps.

08. A woman and her child walk toward a barricade in the Muslim quarter of Sittwe. Rakhine people are allowed to pass through the area, but the Rohingyans are confined within the “ghettoo”.

09. Rohingyans in Aung Minglar, the Muslim quarter of Sittwe, reach for aid handouts of sweet milk for the celebration of the Muslim holiday Eid.

10. A policeman at a checkpoint of the Muslim “ghetto” of Aung Minglar in Sittwe tries to restrict photography. Although

11. Burma is making claims of freedom of press and information, much of the old restrictions remain in place for journalists.

Andrew Stanbridge has been travelling and photographing throughout Southeast Asia for the past ten years. With a vested interest in conflict and its aftermath, Stanbridge focuses on the stories of rehabilitation that are often ignored by the mainstream media. His work has been supported by grants and exhibited and published all over the world. He holds a Master of Fine Arts from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and Tufts University, and continues to lecture at universities about the aftermath of war. In 2002, Stanbridge spent a year in Chiang Mai on a Fulbright scholarship working on a photography project about the modernisation of Thailand using handmade cameras, polaroid film and digital technologies. This series of photos will be used for the Wall Steet Journal, Vice, The Beast and NBC. www.andrewstanbridge.com