Chiang Mai’s journey towards UNESCO World Heritage status has never been about ticking boxes or chasing a label. Instead, it has been a long and very complex careful negotiation between past and present — one that asks a difficult question: how do you protect a city’s heritage when that city is still very much alive?

The process officially began in 2015, when “Monuments, Sites and Cultural Landscape of Chiang Mai, Capital of Lanna” was placed on Thailand’s UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List. The title alone hinted at the challenge ahead. This was not a single monument or archaeological site, but a layered urban landscape shaped by faith, geography, water systems and daily life over more than seven centuries.

Unlike Thailand’s existing World Heritage sites such as Sukhothai and Ayutthaya, Chiang Mai is not a historical park. It is home to residents, monks, markets, traffic jams and morning alms rounds. Any World Heritage nomination here would have to prove not only historical value, but a credible plan for protecting that value while allowing the city to function.

The beginning…

Citylife published an article in 2019, titled, Our Journey to become a UNESCO World Heritage City, writing that Chiang Mai had been placed on the tentative list in 2015, with results expected around 2025. We published at the time,

“According to Dr. Richard Englehard, a former Regioal Advisor for UNESCO who has helped around 200 sites around the world achieve the coveted status over the years, this ambitious mega project has the ultimate goal of strengthening and benefiting the roots of the city. “It is a long-running fight against the rapid and unruly development of the city,” explained Engelhardt who is also a Chiang Mai resident and proving to be a formidable ally and asset to our bid. “Unlike historic sites such as Ayutthaya or Sukhothai, Chiang Mai is a living breathing city, with all the urban complications that goes with it. Therefore at the heart of this project are the people. We want to see a quality of life that is greener, cleaner, quieter, less polluted; a continuation of the generations of development that has gone into what makes Chiang Mai unique.”

Engelhardt explains that each year a country can propose only one site to the committee which will only consider 35 sites worldwide. Chiang Mai is not the only site to be on Thailand’s tentative list and he urges authorities to avoid having Thai sites jostling against one another, but to follow China’s model in queueing them up by priority and possibility. “China has queued nearly 100 sites to be submitted over the next 100 years,” he said, while explaining that Thailand still has yet to decide which site would be submitted next. That decision is made on a national level and will depend on which site is most likely to be considered.

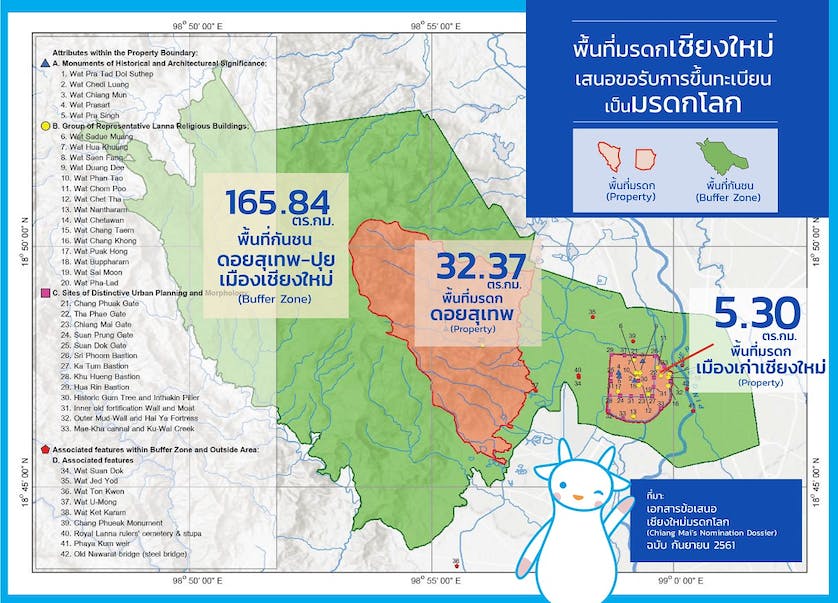

Chiang Mai will be proposed for inscription on UNESCO’s World Heritage List as one property consisting of two complementary components: the historic old city extending to the outer walls and moat including Mae Kha canal (5.30 sq.km.) and the sacred mountain of Doi Suthep, within a buffer zone which covers much of the Doi Suthep-Pui National Park area (165.84 sq.km.). It is a little known fact, but the national park was declared a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in 1977, which means that it is already in compliance with some of the organisation’s rigorous conservation standards.

“A dossier comprises around 1,000 pages,” explained Engelhardt, an old hand at compiling and scrutinising such dossiers. “There are three major sections — the narrative, proof of authenticity and integrity, and the management plan.”

Our Story

The challenge of crafting a successful nomination, according to Engelhardt, was threading together the chosen criteria into a compelling story of “outstanding universal value” — that is to say, a local narrative with global significance. “The committee wants to know how a nominated town has contributed to a global story of interest to the entire international community,” he explained at the time. “In the case of Chiang Mai, I think the components of our story are very clear. First and foremost, is Chiang Mai’s original and unique urban form, designed by the famous Three Kings: Mengrai, Ramkhamhaeng, and Ngam Meung. This ’new city‘ enabled a new, ethnically-diverse and culturally-rich, society to take shape — a civilisation that today the world recognises as Lanna Culture. Lanna Culture is, of course, one of Southeast Asia’s most distinctive cultures, especially renown for gorgeous decorative arts and resplendent temple architecture. To understand how this all came to be, it is important to contextualise the development of Chiang Mai within the historical events swirling around the region when the Three Kings founded their ‘new city‘ in the late 13th century CE. At this time, Kublai Khan, all-powerful Mongol emperor of the newly founded Yuan Dynasty of China, was embarked on a ruthless campaign to expand his territory by systematically attacking the older smaller kingdoms of South East Asia. The Chinese Mongol army had just sacked Bagan and it was obvious that next on the list was to be Sukhothai. Sukhothai’s King Ramkhamhaeng needed an ally willing to build a fortress strategically closer to China, because he knew that if the invading forces made it down into the Ping and Mekong river valleys, not only Sukhothai but all the smaller Tai kingdoms to the north would be lost. The Three Kings concluded a strategic alliance and built the ’new city‘ of Chiang Mai to be the much-needed advanced fortified settlement to thwart any possible incursion by the marauding Mongols.”

Engelhardt explained that what made Chiang Mai so unique was the combination of urban design influences which were drawn upon to build the city. “First, like most cities in the world at that time, spiritual beliefs and cosmology greatly influenced urban planning. The choice of the setting of Chiang Mai at the foot of the sacred mountain of Doi Suthep, was based on ancient local Lawa beliefs in the power of the mountain’s nature spirits. These indigenous Lawa beliefs were reinforced by Mon cultural beliefs in the protective power of the Buddha, especially the protective power of the Buddha relic enshrined on the mountaintop temple of Wat Phra That Doi Suthep. It is also important to recall that, at this time, the famous Emerald Buddha was enshrined in Wat Chedi Luang at the very heart of Chiang Mai, making the new city spiritually invincible. Many of Chiang Mai’s unique cultural traditions and customs, originating from the time of its founding are still being faithfully followed today — for example, the Inthakin City Pillar ceremony. But in their wisdom, King Mengrai and his allies did not rely on spiritual power alone for their protection. Chiang Mai was designed using state-of-the-art knowledge in hydrological engineering derived from Khmer technology, thanks to the contribution of King Ramkhamhaeng to the new city’s urban design. Chiang Mai’s Khmer-influenced water management system, was highly sophisticated and showed great understanding and foresight, thus enabling Chiang Mai to continue to function as a sustainable city even as it has grown exponentially in size from the small town of the 13th century into the urban metropolis it is today. And lastly, Chiang Mai’s high walls, strong gates, and deep moat were modeled after the architecture of fortified Chinese military garrison towns. It is this confluence of disciplines that makes Chiang Mai an unique city, not only in the north of Thailand, but in the entire world — and therefore part of the global story of urban design and development, worthy of inscription on UNESCO’s World Heritage List.”

The Chiang Mai story doesn’t end with the 13th century, according to Engelhardt. “The 18th and 19th centuries saw an explosion of art and architectural abundance in the city. Again, Chiang Mai’s story is both unique and globally connected. As Europe’s shipping empires grew, the great ships needed big, long, sturdy masts. And there was no other wood better than teak. Chiang Mai had an abundance of teak and unlike other commodities there was no shortage of it in local supply. And because there was no immediate need to reinvest in planting teak, as the trees were abundant in the surrounding mountain forests, so Chiang Mai’s local teak merchants accumulated vast surpluses of wealth — wealth that they reinvested in the lavishly beautiful temples of the city that had made them rich. The result of this is what we see when we look around at gilded pagodas and glittering temples — a surplus economy based on rich profits made by local teak merchants who supplied valuable, strategic material vital to the development international shipping and commerce. Understanding this, we can understand that Chiang Mai’s long and continuing story of prosperity isn’t just a temporary local phenomenon or a consequence of the city’s link to regional economic fortunes, but because the city had a far greater reach as an indispensible link in the chain of global trade and development.”

According to Asst. Prof. Komson Teerapapong, from Chiang Mai University’s Faculty of Architecture, one of the many researchers tasked with writing and verifying submitted data

on the city. “We can’t just say that our city was founded in 1296 or that this temple was the oldest in the city; we have to prove it. UNESCO’s standards and values are very high.”

“Chiang Mai must deliver proof, challenging all of the history books to prove its authenticity,” he continued. “As to integrity, this is the hard bit as it is about showing how intact a building is. Wat Phra Singh, the wall, or gates for instance, have been renovated so many times over the centuries, so you have to look at how they have been repaired, and what techniques used to rebuild.” He goes on to explain that the World Heritage Committee has adjusted its guidelines over the years, giving space for living cities which have evolved with societies. “Now that we have declared our valuable assets, the next question is how to preserve it. And with that comes the management plan. As a nominated living heritage, the concept of sustainable development will be pulled into the plan along with the conversation,” added Komson.

A Living Cultural Landscape

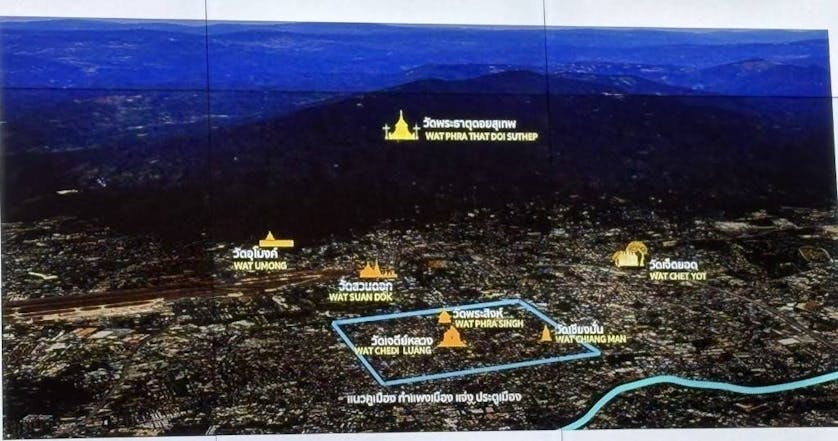

At the heart of Chiang Mai’s nomination is the idea of a cultural landscape — a place where natural features and human activity have evolved together. The proposed World Heritage property links the old city, its moats and gates, and a network of significant temples with Doi Suthep, the mountain that has defined Chiang Mai’s spiritual and physical orientation since its founding.

The nomination includes seven major temples — Wat Chiang Man, Wat Phra Singh, Wat Chedi Luang, Wat Phra That Doi Suthep, Wat Suan Dok, Wat Jed Yod and Wat Umong — along with five city gates and four bastions of the ancient wall. Together, they tell the story of Chiang Mai as the former capital of the Lanna Kingdom and a centre of Theravada Buddhism that continues to shape daily life.

From Concept to Commitment

Over the past five years, the UNESCO bid has moved steadily from concept to concrete action. Researchers, conservation experts, monks, local authorities and civil society groups have been involved in surveys, consultations and planning sessions. Discussions have ranged from temple conservation and skyline controls to signage, traffic, visual clutter and how modern development can coexist with historic space.

A major turning point came in January 2026, when the Thai Cabinet formally approved the submission of “Chiang Mai, Capital of Lanna” to UNESCO as a cultural landscape World Heritage site. Shortly afterwards, provincial authorities confirmed that the full nomination dossier had been officially submitted to UNESCO, pushing the process into its most critical phase.

At a working committee meeting held at Wat Chedi Luang on 17th January 2026, Chiang Mai Governor Rattaphon Naradison described the next stage as a shared responsibility. Preparations are now underway for an inspection by the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) — UNESCO’s advisory body for cultural heritage.

The Test Ahead

ICOMOS experts are expected to visit Chiang Mai around mid-2026, assessing not just the physical condition of historic sites, but the city’s management plans, legal protections and — crucially — community involvement. Their evaluation will feed into discussions at the UNESCO World Heritage Committee meeting in November 2026.

The challenge is significant. Chiang Mai would be Thailand’s first World Heritage city that remains fully inhabited, meaning success depends as much on how the city is managed day to day as on its historical value.

More Than a Title

For those involved, the UNESCO process has never been about prestige alone. Whether or not Chiang Mai ultimately secures inscription, the journey has already forced important conversations about urban identity, conservation and what kind of city Chiang Mai wants to be.

World Heritage status, if achieved, would bring international recognition. But perhaps more importantly, it would offer a long-term framework for protecting Chiang Mai’s cultural soul — not by freezing it in time, but by ensuring it can continue to evolve without losing what makes it unique.