It’s 5 a.m. and I’m awake. I’m putting on athletic shorts and sneakers because I forgot to ask what to wear and this is my “who knows?” go-to ensemble for unforeseen, vaguely physical activities. In less than an hour I’ll be speeding through the mountains of Doi Saket behind a 50-something Dutchman on a motorbike. We’ll be hunting for snakes.

The Man, the Myth, the Legend

Sjon (pronounced like “Shan”) Hauser came to Thailand 25 years ago as a traveller and writer. Originally schooled in biology in his native Holland, where he says he did a lot of work with rabbit brains, Sjon’s first Far East foray led him out of the laboratory and into the exciting field of travel journalism. In his early expat days, Sjon wrote countless articles and several best-selling Dutch language travel books about Thailand and Southeast Asia. With a particular fondness for nature and a growing amount of acquired knowledge on the intricacies of Northern Thailand’s flora and fauna, he also worked (and still works) as an offbeat environmental tour guide between jobs to make some extra money.

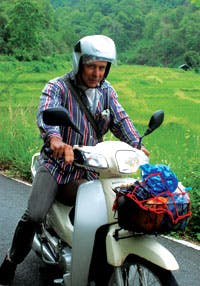

Today, Sjon dedicates most of his time to what has turned out to be his life’s greatest passion: snakes. To call him a bit of a fanatic would not be unfair. Now in his mid-50s, with a kind of rugged, aging handsomeness, receding blonde hair and boyish blue eyes, Sjon lives alone and is semi-retired, but keeps himself very busy, spending at least two or three days a week hunting for snakes in the mountains and jungles of Thailand, and the rest of his time studying and writing about snakes. Why? The reason is simple. He just loves it.

“When you find something you’re passionate about, it’s like a fatal disease,” says Sjon. “You can’t get rid of it.”

Sjon’s work is not in vain, even though it doesn’t exactly pay the bills. Recently, he was able to discover a whole new snake species called the Saw-tooth-necked Bronzeback in Tak Province, which after a great deal of work was accepted by the taxonomic journal Zootaxa in 2012 (not an easy accomplishment, to be sure).

“Unfortunately, I don’t get paid to write articles for scholarly journals and my books don’t sell much anymore. Nobody reads books anymore! It’s all on the internet! But I have made some interesting discoveries that I hope will add something to the world, and change the way people think about snakes,” says Sjon with a shrug. “Everyone wants to think that their hobby is useful.”

Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps)

Worldwide polls have shown that ophidiophobia, or the fear of snakes, affects up to 50 percent of all adult humans, making it perhaps the most common phobia in the world. And those who fear snakes often do so in a highly abstract way, even when no true physical danger exists. Viewing a picture or even the mere mention of these creepy crawlers can set them off.

According to an oft-cited 2001 study in the Journal of Experimental Psychology, these fears have been shaped by evolution, dating back to a much earlier period when mammals had to survive and reproduce in an environment dominated by potentially deadly reptiles. A more recent 2008 study at the University of Virginia noted the ability of preschool-aged children to immediately identify snakes amongst other non-threatening stimuli as quickly as their parents could, suggesting that humans’ fear of snakes could be intrinsic.

In short, people and snakes have a long and complicated relationship, dating back to the earliest mammals, both scientifically and biblically – we all know the story of Adam and Eve and what happened to them when they got friendly with Mr. Legless. But a deeper, perhaps not so devout reading of the Bible might suggest that what Eve’s serpentine dealings brought was actually positive: knowledge and mortality – the very things that make us human.

For Sjon, the latter is most definitely true, and he hopes that the work he is doing with his slithering friends will help address society’s generally needless and overblown fear of snakes. “One dream of mine is to open my own snake farm,” he says. “Most of the farms around here, they focus more on the show. They don’t tell people anything useful about the snakes – it’s more just like ‘ooh, big scary snake, watch out!’ This just adds to the reactionary fear that people already have. I think they are missing out on an important opportunity for sharing knowledge.”

In truth, of the 85 snakes species in Northern Thailand, only 15 are very poisonous. 10 to 15 are mildly to moderately poisonous, and the rest are harmless. Furthermore, says Sjon, even the most poisonous snakes tend to be more scared of you than you are of them.

“In the past, many people were killed by cobras in Southeast Asia and India, causing an inborn fear of snakes,” he notes, alluding to the 2001 study. “Today, the fear itself is more harmful than the actual snakes. Thai people know nothing about snakes. When they see one, they often try to kill it, which is the worst possible reaction for several reasons. One is that the snake is most likely harmless anyway. Two is that by trying to kill a poisonous snake you are just increasing your risk of getting bitten. If you just leave it alone, it will leave you alone.”

The only exception is a female king cobra protecting her eggs. Mothers are ruthless when it comes to protecting their young, as we know, so if you approach within ten metres of a king cobra’s nest, the mother who is guarding it may notice you, attack, and inject so much venom that you’ll die in minutes. To illustrate, Sjon tells me a charming little story about a couple of students in Khon Kaen in the 1980s who found a nice isolated spot to have sex in the forest near campus, just next to some sewer cylinders (ah, young love). They disturbed a female king cobra’s nest, causing mama cobra to bite the boy in the butt mid-coitus. The terrified girl ran back to campus to alert the authorities, but when they arrived less than half an hour later, the boy was already dead.

“It’s that quick,” says Sjon. “But this is a rare case. Typically, my advice is to be careful, but not hysterical.”

Roadkill Safari

Luckily, I am not ophidiophobic. In fact, I tend to be rather fearless to a fault when it comes to animals (bugs are another story, for another time). That said, there is one thing I forgot to mention about this little road trip of ours: the snakes we would be hunting were mostly already dead.

Obviously, it is easier to catch and study snakes when they are already incapacitated. But the thing to note here is that Sjon is only a hunter in the fractional sense. Most snake hunters (most being a relative term, as this is not exactly the world’s most popular profession; in fact, Sjon is the only one he knows of here in Northern Thailand) tend to do their searching at night with flashlights, to catch and kill snakes during their most active period. Sjon, on the other hand, never kills snakes, at least not intentionally. (“I ride my motorbike a lot, so I’ve probably squashed a few, but I’ve saved more. So we’re okay.”) He figures that with so many bad drivers on the roads, the real work is already done for him. All he needs to do is collect the results.

So that is where we are now: my first ever roadkill safari. Welcome to it.

A few kilometres into the foothills of Doi Saket, Sjon stops suddenly and pulls an impressively tight U-turn. “False alarm!” he says, after another look. “Just a piece of rope.”

We ride on. The views are breathtaking, and I find myself feeling a little guilty about how rarely I allow myself to see Thailand at this time of day, when the air is still cool and the mists wash over the green mottled mountaintops like cappuccino foam. Stray dogs on unbeknownst missions trot by old men on bicycles, saffron-robed monks bearing silver alms bowls and chickens pecking in the roadside dust.

Screech! Snake number one is flat as a pancake and reeking. “Ah, a kukri snake,” says Sjon knowingly, although I hear “cookie snake” and spend the next hour wallowing in potential puns until I am corrected. “I caught a beautiful live one for you last week but I put it in an old cage at my house and it escaped,” he continues nonchalantly. “Oh well.”

Snake number two is another long-dead stinker, followed by a flattened frog and a sufficiently gross eel-like creature. “Very common, live in the bushes. They come out after it rains. See, they have no scales. They’re amphibians,” notes Sjon before tossing the thing to its final resting place, a clump of roadside bushes.

He shows me his mobile snake study kit – a magnifying glass, a measuring tape, plastic bags, a bottle of alcohol for preserving anything particularly special (“not my morning piss, contrary to what it may look like”) and a rock (“for the nasty dogs if they chase me, as they often do”). So far, the dogs have left us alone and we haven’t collected anything. Back on the bike.

We pull over again at a pretty riverside vista in Mae On. Sjon points out the spot where in more fruitful times he found a particularly rare breed of water snake, originally discovered in 1918 by friends of King Rama VI’s royal physician, the great Southeast Asian snake expert Dr. Malcolm Smith. The species had never been seen since and was assumed extinct until Sjon found another one in this very spot just last year.

“Sometimes people give up on certain species, when it turns out they are just very good at hiding,” he says.

Next we come across a nearly-dead lizard called an agame. Sjon pronounces it “a good sign” and plops the poor bastard into his motorbike basket. The agame utters a final gasp before succumbing to its new role as our tragic little mascot, mouth agape, tiny clawed hands (do lizards have hands?) limp at his sides. (I am clearly way too emotionally affective for this sort of hobby.)

Good signs aside, the rest of our journey up the mountain is reptile-free. Things are starting to look a bit grim. Sjon’s shoulders slump a bit as we wind our way through the steep mountain roads and a light rain begins to fall. Near Doi Lung Ka we step out of the car to admire what he says would be a beautiful view, if not for the thick white fog enveloping us like a cold, wet blanket. Sjon points out the rocky grottos where wild white orchids will bloom in a few weeks and where wild snakes undoubtedly hide from the chill. We stop for soup at a roadside village next to a small coffee plantation. It begins to rain harder.

“Well, let’s head back down,” says Sjon. “Not every day is a success.”

Here Comes the Sun

As we wind back down the mountain, the rains recede and the sun emerges – finally. We spot a long-crushed striped keelback by some picturesque rice paddies. Not a noteworthy catch, but a nice spot for a photo op. Then, a fly-covered checkered keelback, also long dead (and thoroughly revolting) but strangely placed just centimetres away from an equally-flattened, equally-fly-covered scorpion, like two star-crossed lovers in a suicide pact.

“Strange pairing,” says Sjon. “Sometimes you’ll find a mouse and a snake crushed together, since the snake will often bite the mouse, let it die of venom poisoning and then begin to swallow it hours later, only to be crushed by a car mid-swallow. I don’t think this keelback was hunting a scorpion, but you never know.”

I like my theory better.

We’re back in civilisation now, passing petrol stations and car dealerships on the road to Chiang Mai. It’s looking like the day will end rather thanklessly, without any usable finds. I’m brainstorming ways to write this article anyway, something about crushed snakes and crushed dreams…

Then suddenly, another screech. Sjon U-turns and emerges in the rearview, smiling like a kid on Christmas, a metre-long snake swinging triumphantly over his head like a helicopter. He refuses to repeat the move for a photo (“I don’t usually do that”) but holds up the specimen for a closer look. Aha! This one is not pancaked or dried out or doused in flies. In fact, it’s still bleeding, and the fact that this actually excites me is a tribute to the infectiousness of Sjon’s own enthusiasm. I even willingly reach out to touch it – it’s cool and smooth.

“A checkered keelback, freshly squashed just an hour ago, at most,” announces Sjon. It’s not a rare species, but a good find, worth taking home and skinning or preserving the tail for DNA. Sjon straps it into the basket alongside the agape agame (another unlikely duo, later to be discovered with horror by the staff at the next petrol station) and we hit the road again.

I feel an odd sense of satisfaction. It has been a day unlike any other day, and we’re not going home empty-handed.

To learn more about Sjon or to book your own nature tour, visit www.sjonhauser.nl