For most of us it is hard to imagine anything as inhumane, or more unjust, than the infliction of cruelty upon a child. The spectre of a child whose life is starved of innocence from the start is a saddening sight; the child becomes in some ways a ghost of who he/she may have been had they not had to endure the vagaries of an unfortunate beginning. Life for street children is often pervaded by exploitation, it is engineered by poverty, inimical demands; bereft of kindness, love, hope. It is perhaps the nadir of human tragedy when children are not allowed their human right to exist as children should, allowed to inhabit their own curious world, to be playful, to be reckless . . . to be both vulnerable and safe.

Dek ray ron (loosely translated as vagrant children), or street children, are a common sight in Chiang Mai. Many of the kids will have come from Burma, or perhaps from a hill tribe; most of them won’t have Thai ID. The children and their parents perpetually run the risk of being deported, except it is not the parents who are usually intercepted on the streets, it is their children for whom unpaid labour, or begging, is a daily way of life. Some street kids are trafficked into Thailand by criminal organisations whose malignant quest for profit and total disregard for human suffering cannot be underestimated. Street children will most often find themselves trapped in a life, rather than living one, and the maze of exploitation in which they find themselves sunken into, has few, if any exits.

A representative from HOTS (Heart of the Street), an organisation working to combat the child sex trade, acknowledged that, “In the face of indifference, these children will continue to live as street kids.” He added that many street kids find their way, or are sometimes enlisted, to work in the sex trade. “Against a backdrop of corruption they will remain pawns in the game of profiteering from their misfortune . . . these kids will continue to struggle with no direction or real purpose…”

Perhaps a reflection of the difficulties inherent in trying to help street children is the fact the internet lists a handful of organisations that opened with the intention of charitable exercise, that no longer exist. “Philanthropic foreigners with their well-intentioned but short-sighted projects have much to answer for helping perpetuate the problem for these kids,” he stated, adding that “local government offices inefficiently deal with the issue of the street kids, local NGOs are often understaffed and lack resources and appropriate training in child protection measures.”

There are thought to be around 20,000 – 30,000 street children in Thailand, most in Bangkok, Pattaya and Chiang Mai.

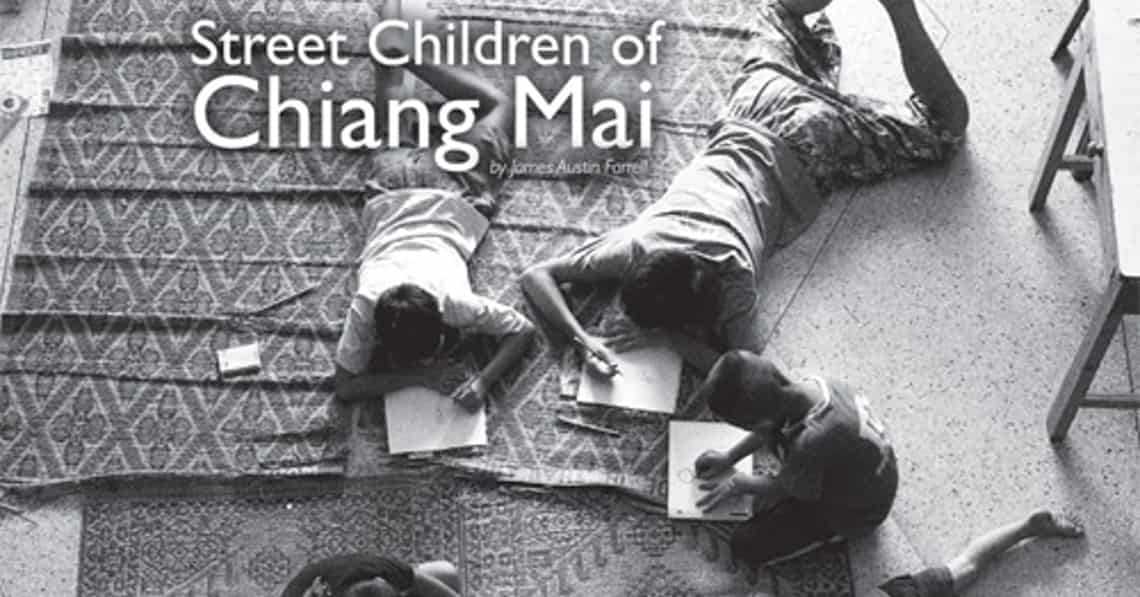

One local NGO, VCDF (Volunteers for Children’s Development Foundation) has been a continual source of help for Chiang Mai’s street children, empowering, educating and protecting them from the many dangers they face each day, as well as offering them healthcare, activities and shelter. Their drop-in centre is noisy, hectic, and dotted with children’s drawings and educational books. UNICEF (supporting agency) posters are stuck to the wall, quite comically scribbled on and adapted by the VCDF’s own children; a maelstrom of (mostly) sun scorched kids aged around eight to seventeen study, play and sleep.

Aek, the founder of VCDF explains that almost all the kids have parents living here in the city slums. The younger kids are often forced to sell flowers at night or beg, and often their parents are unsupportive of anything other than their child’s earning potential. Only a few of the children have no parents and stay at the organisation, while other children are sent to a home out in Sankampaeng where they also study at a government school. Aek seems distracted when first meeting us; he seems distant, looking at us with an air of suspicion. Street children have been targeted and will be targeted by paedophiles and traffickers, it is with great caution that volunteers working with street children deal with outsiders.

Aek explains, “The kids often want to help their families, but sometimes they get bored begging. When they are older some of them turn to sex work, especially the boys.” Paedophiles, he says, both Thai and foreigners, seek sexual gratification from these children. Unless the kids are ‘rescued’ at a young age, many he says, will end up soliciting sex, on drugs, or in jail. “We are trying to develop them,” he explains, and adds that some of the ‘peer leaders’ volunteering at VCDF have managed to stay clear of drugs and prostitution. The centre is in its thirteenth year now and Aek has seen some of these kids evolve from beggar to teacher. But just a handful of these kids, he says resignedly, will evade a bleak future.

A third of the people in Thailand live on less than US$2 a day and in the agricultural northeast one in six people lives on less than US$1 a day.

An ongoing and seemingly intractable issue is how the local authorities deal with kids and their families who have no Thai ID. Children are often pulled off the streets by the police, only to be sent to a government shelter, where often, Aek explains, they escape. “They don’t like it there, they want their freedom.” If the parents are arrested too they will be imprisoned and then sent back to Burma. He explains that every so often, mostly during big festivals, the police decide to crack down on street children – a kind of war on street kids – and ‘clean up’ the city for the sake of visiting tourists’ impressions. “When they see the police,” he says smiling with affection for the children, “they run for it,” explaining that this life on the run is their everyday reality. Two young boys at the foundation called Ae and Oh, nine and ten years old, have had to learn to live a life on the run after being thrown out of home by their stepdad. They both possess a precocious maturity, and almost fatalistic independence that you don’t usually see in boys this age. “We worked in a monkey farm in Lop Buri,” Ae says, “and we got 20 baht a day.” He seems quite proud of this fact. They managed to get to Chiang Mai through a guardian and now both attend a government school and study at the foundation.

Even with the opportunity to go to school, for many of the children – having to work at night and take frequent trips to Myanmar – study isn’t really a viable option. An option they do have is to create handicrafts for sale at VCDF’s Arts and Handicrafts for Street Children shop opposite Wat Phra Singh Post Office. All items are made by the kids who receive payment while profits also go back into the foundation. Begging children, according to Aek, can make up to 1000 baht a night for their parents or unscrupulous ‘guardians’ – sometimes supporting a drug/alcohol habit, or saving money to take back to Burma in the future. Right now, he says, the kids working on the streets are making very little money as tourist numbers are low, starkly he adds, “sex tourism is low” too, which has affected a personal economic downturn for some of the older kids. Nevertheless, some of these older boys at the centre sleeping on the floor, Aek points out, will most certainly have spent last night on ya ba while ‘servicing’ foreign men. As a girl, aged nine, tells us how she used to beg, but now just wants to go back to Burma; and as a jaunty young boy explains how he doesn’t want to go back to Burma, rather open a snack shop here in the future, it is sobering to see three older boys (who were also at one time ‘young vagrants’) lying on the floor a few metre’s away, sleeping off a night of methamphetamine and (masqueraded) homosexual prostitution. Granted these boys made an independent decision to sell their bodies, and will be remunerated (relatively) handsomely considering their realistic alternative employment options. But as their young counterparts gather around us, it’s hard to defend their ‘free choice’.

Over the last decade new initiatives have attempted to arrest the preponderance of touristic and local paedophilic-based prostitution in Chiang Mai, though Aek explains that the legal system is still not competent enough and much more can be done. “It depends how the law is enforced,” he says sceptically, an allusion to the law’s capricious nature.

A Chulalongkorn University report gives a total of 2.8 million sex workers, including 800,000 minors under the age of 18 in Thailand.

Rossukon Tariya, Secretary of the Implementation Committee and the Chiang Mai Coordination Centre for the Protection of Child and Women Rights (CCPCWR) explained something of government policy concerning street children. “As of the Child Protection Act 2003 we must work to protect all children in Thailand,” adding that children of all nationalities are subject to this protection. She explained that the police and all other organisations working with street children must work according to the ‘Convention of the Rights of the Child’ (CRC) and follow international guidelines and procedures, as well as working within Thai constitutional law and Thai immigration laws. “We have to integrate the laws,” she explains, adding that “what is best for the child” is always their first concern.

But the integration of the law and the complicated issue of ‘what’s best’ for each child can often be a demanding problem. As each case of a child found working on the streets is different, each case must be ‘identified, investigated and accessed’, which is a lengthy and difficult task. “We have to arrest the mother and father,” she says, “if the parents are here illegally.” Though begging is not a crime in Thailand, the parents are only guilty of immigration transgressions. The child is often taken to a shelter while the parents are sent to jail. The child in every case will be allotted a social worker (a statute of the Child Witness Law) and questioned by the police. If the centre deems that the child should be sent back to Burma with his parents, then along with the social worker, the family is taken back where they’ll be met by a Burmese social worker or NGO representative. The recurrent problem is, they’ll “come back into Thailand again and again,” according to Rossukon. She explains that Thailand cannot just allow anyone to come across the border and work, immigration laws must be adhered to in spite of any sympathies a person or organisation may have towards the family.

In some cases it is better for the child to remain in Thailand – trafficked children for instance – where it is possible by law for the child to receive a full Thai education. Sometimes children are trafficked into Thailand to work for a Thai family (not sent to school in most cases) to labour in homes or factories, and though not specifically sent to work as sex workers, “some of these kids suffer sexual abuse,” says Rossukon, and child labour is also illegal in Thailand under the Child Protection Law. The centre, along with NGOs and police are working to curtail the activity of the gangs that traffic the children for all manner of pecuniary motives. She explains that it is very difficult to work with NGOs and families on the Burmese side, and that a bilateral agreement with Burma on this matter is still not fully implemented.

Police, with the help of CCPCWR and local NGOs have recently arrested paedophiles in Chiang Mai, including one foreigner, a monk, and a Thai man who was a crime boss involved with child trafficking and also guilty of sexual relations with children; he had “recruited kids from the streets” and imposed himself as their ‘father’ while initiating them into servicing other paedophiles from his house. “It’s a cycle,” Rossukon admits, “with no social welfare in Burma this will keep happening, children and their families will keep arriving in Thailand.” More and more children, under an umbrella of poverty, will be thrust into this vicious ‘cycle’ while conditions in Burma force the parents to cross borders or sell their children from home. While NGOs, government offices, police, attempt to staunch the activities of the many exploiters and help to protect the lost children, the roots of the problem, mainly abject poverty and its stifling corollaries, seem irremovable.

VCDF is not supported by the government and is direly underfunded. They need “anything” Aek says: books, toys, clothes, teaching equipment, audio/visual equipment, cups, saucers, literally anything the centre or kids can use. Money is of course also needed. Volunteers who might teach in any capacity can contact the centre. Because of the nature of the job, you will need a police clearance from your country, credentials, references and teaching experience.

TRAFCORD (Anti-Trafficking Coordination Unit Northern Thailand)

Report paedophile activity: call 1300 during daytime hours and 081 307 2111 (be sure you are certain there is criminal activity and try and submit as many details as possible)

The names of the children used in this story have been changed