“Thais are not allowed to have fun with traditions,” said Philip Cornwel-Smith, author of the wildly successful book on Thai popular culture, Very Thai, now in its 10th printing and second edition. “It is very difficult to go against the master template, so Thais have always got their novelty from bringing in things from the outside. Being very receptive to imports, Thais have fun with it. God forbid you have fun with traditions!’

Philip has a knack of saying something obvious, or seeing something interesting, that hadn’t been said nor seen before. Which is why his book, published in 2005 (and seen prominently displayed in every bookshop nationwide ever since), took the country by storm. Here was this Englishman showing us Thais an embarrassment of cultural riches that had previously gone unappreciated. It was discombobulating, inspiring, empowering and most of all sanuk.

Having studied word history at Sheffield University, where the focus was less on wars and nation building, and more on culture, invention, religion and other such factors that build and destroy nations, followed by years working for Time Out London, Philip had a solid background in looking at culture from different perspectives. Serendipitously, on a layover in Bangkok on the way back from Australia in 1994, he was asked to start Bangkok’s first city listings magazine, Bangkok Metro, which would a focus on popular culture.

“Within four days of being in Bangkok I found myself editor of a city mag which soon had 1,000 listings,” said Philip. “People were instantly shocked to learn of so much variety in the city. The transport problems in those days meant that it took two hours to travel from Ekamai to Lumpini, so most people didn’t venture far out of their five or six known areas. But when they saw in Metro how many things were going on, they began to venture further. The mag was all about pop culture. I was coming at it with outside eyes, but it didn’t take long to become a semi-insider. With my background, I had a view that popular culture is an attraction that people would travel for. Up to that point it wasn’t treated with the seriousness of formal culture; there was shame associated with street life that city-sophisticates were embarrassed by.”

As not just an observer, but an influencer of Bangkok’s pop culture, by the time Philip left Metro in 2002 he had begun to put down thoughts and ideas that would eventually come together in Very Thai.

“I’d become fascinated by then-obscure things such as the ecology of the streets,” Philip explained of how his book came about. “In Thailand so many things are to do with rice and monsoon cycles, and this explains so much about the people, especially the need for village communities to develop in a reciprocally helpful way. This value was brought to the streets of Bangkok with the mass migration of rural people into the city. The co-op ethic is vastly different from the formal bourgeois attitude of the urban people: open shop houses, street vendors looking after one another’s stalls and even kids, motorbike taxis being socially helpful by directing traffic, running after thieves and delivering packages. It is a reciprocal village value but in the big city, which gives Bangkok a warm charm you don’t get inside the malls.”

“I wrote the book thinking there would be a market amongst expats like me,” he continued. “But I was as surprised as anyone at the massive splash the book made. Immediately the biggest and most loyal fan base became the young Thai Indies in the creative industry. I have been told that the book was almost definitive for them; they had been aware of these things, but because pop culture wasn’t treated seriously, they weren’t legitimate topics to work with. Suddenly low culture was put into a high culture format — an illustrated hard cover book — it was like putting something lowly on a high-status plinth. It suddenly legitimised these things and opened them up for exploration.”

Very Thai asked questions and attempted to offer explanations for such random and obvious things as the Thai sniff-kiss, why Thais use those ubiquitous thin pink napkins, why motorbike taxis wear different coloured vests, and what’s up with all the neon lights?

“A lot of these things soon became cultural signifiers,” said Philip. “The idea that middle class Thais would go around taking photos of street vendor carts was absurd until the book came out. Today you have places like Plearnwan in Hua Hin which is a virtual theme park for such streetlife. What was interesting to me was that none of it was wholly traditional and none of it was modern. It was all hybrid. Look at the neo-classical architecture of shop houses, or the vehicles decked out in auspicious décor. Tuk tuks were originally Italian, then Japanese, but even though 34 countries around the world use the tuk tuk, they are very Thai. They used to have words such as Daihatsu on them, but after the 1997 crash they started having ‘Thailand’ emblazoned on the back with red, white and blue colours. If you really look at them, they are a short stubby vehicle, but with a real elegance, because they use ancient forms and lines of oxcarts and long tailed boats.

Thailand saw such great change between the end of the Second World War and the early 2000s. It wasn’t a slow cultural change; it was a deluge. This led to a lot of impromptu solutions to things. Especially with the low income people – they began to jury-rig things, and do a lot of improv. This led to a great amount of creativity. You can see this clearly when thinking of the Thai temple fairs. It is little known that they came about when Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram, in the 1950s, promoted them as a way to bring modernity to rural villages. Technology, modern medicine, outdoor cinema propaganda, these were all introduced, as a national policy, through temple fairs. People would then localise them to their own tastes. I have noticed that there are a lot of taboos about updating traditions, but Thais have a natural sense of fun and creativity, so they played around with new and modern imports. It’s quite interesting to see how, whatever the authorities do, simply becomes less fun!”

From observing pop culture phenomena, Philip has just about turned into one himself, with fans of the book sometimes asking to take selfies with him. Very Thai has been subject of numerous artworks and exhibitions and Philip is a frequent guest lecturer at various universities. One designer wrote recently on Facebook, “The defining moments for me as a Thai designer, both in was the mid-2000s. were the discovery of the book Very Thai, and visiting the Isaan Retrospective exhibition at TCDC.”

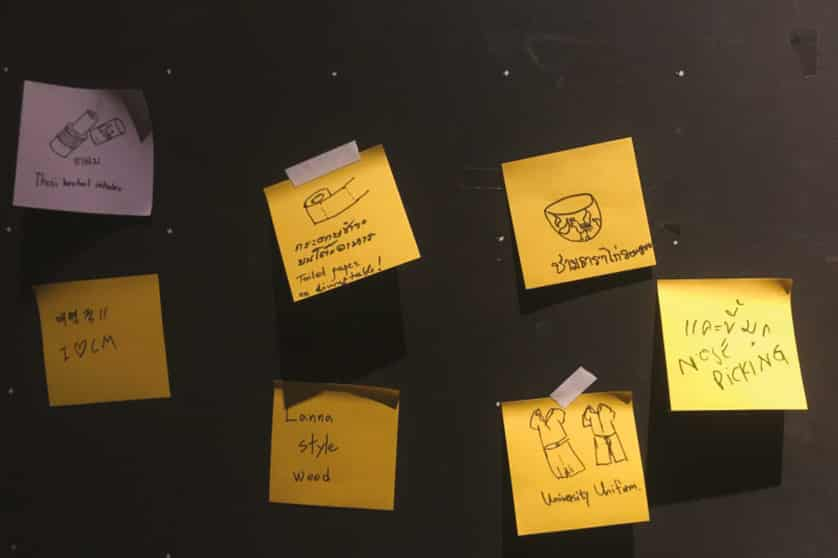

Which brings us to why we have chosen now to interview Philip who, until the end of this month, will be co-curating a fascinating little exhibition at TCDC Chiang Mai called Invisible Things. Together with TCDC and the Goethe Institute Bangkok, Philip and exhibition designer Piboon Amornjiraporn put together a collection of 25 everyday items which ‘we take for granted and no longer perceive, but which in fact influence our consumer behaviour’, according to the exhibition’s booklet. The selection of Thai objects echo a collection of German objects on the other side of the room, curated by Martin Rendel, which are on a tour which started in China.

Displayed are packets of mama found in every single Thai household, the largely unnoticed dragon jars sitting in nearly every garden, the sin sai white strings used in a bewildering number of ways from house blessing ceremonies to greeting a guest, and the omnipresent fisherman pants which Philip describes as Thai to the core, “Many cultures have some kind of wrapping trousers,” explains Philip. “Yet it is known internationally as a Thai thing. I find it very Thai because it is extremely flexible and adaptable, infinitely expandable and practical. It represents Thainess internationally.”

“One classic example of an invisible thing is the red Fanta bottle. Interestingly Thais prefer drinking green Fanta, yet millions of red Fanta bottles are left open on alters, shrines and spirit houses nationwide. Next to flowers and incense they are probably the most common offering. There is no definitive explanation for this so I called my spirit medium friend — as you do in Thailand — and was told that the red represents blood which the low spirits, the demons, like. Other people say it’s simply because the bottles are sturdy and don’t blow over or that spirits want modern pop drinks too. Whatever the reason, they are found everywhere, even by the feet of the Yaksha giants at Suvarnaphumi Airport!”

Philip went on to offer a warning, however, that the era of localising imports into Thainess is nigh. “With modern communication you can get everything instantly. We are no longer a decade behind Milan in terms of fashion, because of YouTube. There is no delay in knowledge getting to Thailand. People want objects in their purest forms and they can both afford them and have them immediately — whether a Samsung tablet or a handbag. Every culture is a hybrid to some degree, but the whole world is facing unrelenting sameness. Because of the ability of digital technology, innovation isn’t happening as much in the physical form. It’s shifted into a different realm, one that’s not tactile. Whereas you used to improvise and create a hybrid, now you just get the thing you need to do the job. It’s samey everywhere. Invisible things are becoming visible.”

Invisible Things Exhibition

at TCDC Chiang Mai

Open 10.30am – 8pm

Tel. 081 833 4566

Until the end of February