Akha Ama, Ristr8to, Wawee, Doi Chang…these are all household names in Chiang Mai, and known for being at the forefront of our exploding coffee culture.

Blogs, magazines, and social media wax ebullience over our city’s deep love and raging passion for all things coffee, with appellations regularly tagged after our city’s name such as ‘South East Asia’s Coffee Capital’ or ‘Coffee City’. So much so that many of us forget that our so called coffee culture, while not in its infancy, is merely in its tweens. Believe it or not, a decade or so ago you would have struggled to find a cup of coffee that didn’t powder out of a sachet, unless you were in a posh hotel.

Yes, His Majesty’s Royal Project did indeed encourage hill tribes to plant coffee, but according to an interview Citylife conducted with Royal Project Director Prince Bhisatej Rajani in November, the crop’s slow yield — requiring three to five years — didn’t catch on as much as it could and although they continued to work with some farmers to grow coffee, the Royal Project initially focused its initiatives on other winter crops such as peaches. Social media is, of course, part and parcel of the popularisation of just about everything these days and has helped spawn and grown innumerable coffee shops over the years, but it still came a bit late in the coffee game; the resulting chicken to the coffee egg as it were. Returning budding baristas have indeed opened up numerous coffee shops all over the city and are integral to its growing demand, but cannot be attributed with the literal ground breaking of the coffee plant. And the same goes with students who in this case were less trendsetter, as trend expander.

The truth is far less sexy as a story, but fascinating nonetheless. It is a story about a brand which may be less known among coffee consumers, but sterling in reputation amongst coffee-related businesses — Hillkoff.

From the Ashes

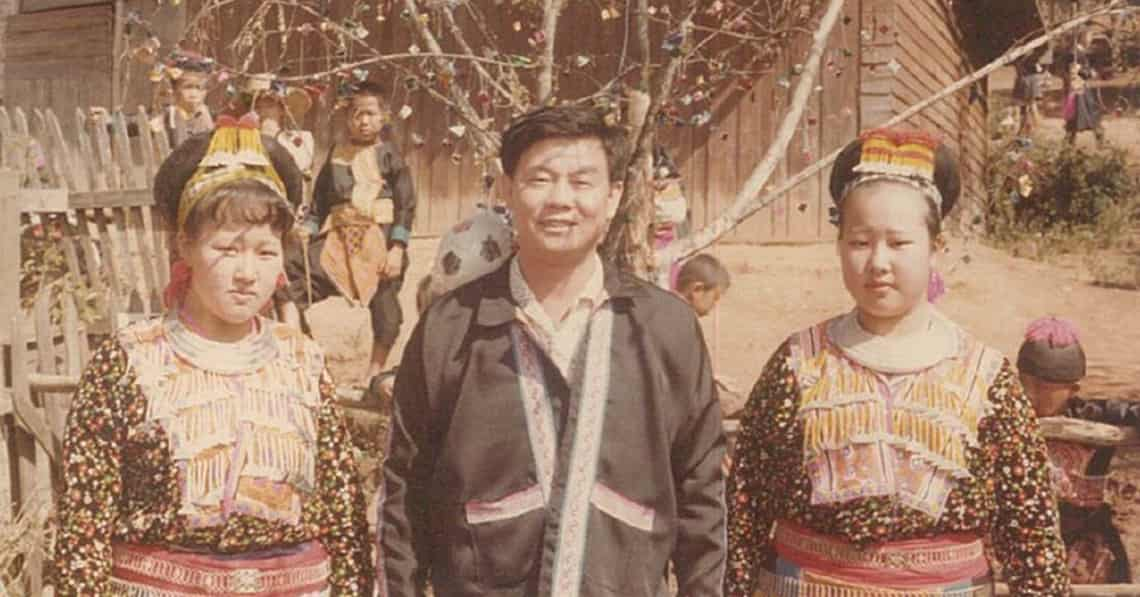

One of 11 siblings in a family which migrated from China, Teera Taksa, 68, the founder of Hillkoff, was a typical Chiang Mai merchant’s son. He attended Montfort College and his parents traded material at Ton Lamyai Market next to Warorot Market, focusing on cloths for hill tribes. “In 1967 a massive fire razed the market and my family lost 80% of all they had,” he recalls. “I decided to drop out of school and help my father rebuild. Incredibly, the hill tribes were extremely loyal customers, this was mainly because most shops in the market wouldn’t even allow them to step foot inside as they were considered dirty, but we welcomed them all, to the point that we even had a house where they could sleep in when they came to town to trade. With their support, we soon rebuilt and our business expanded rapidly.”

Teera soon found himself not just selling, but also delivering, to his customers, often putting together caravans of up to 30 horses and 40 cows, laden with materials and other goods, and heading up the mountains to remote villages.

“My shop’s name was Thai Mountain People,” Teera continued, “which really made them happy as many people didn’t even consider them Thai in those days. We did a lot of bartering, which was helpful to the cash-strapped hill people. When the United Nations began to work with the Royal Project in the early 1970s to find replacement crops for opium they approached me because of my reputation for being connected to the hill tribes. So I was asked to take red kidney beans up to encourage hill tribes to grow them. For a while, this was a success and I ended up buying the beans and selling them to merchants in Bangkok.”

Unfortunately the red kidney beans were not a stable enough plant, being prone to disease, and one year Teera found himself dumping most of his beans into the Ping River. In the meantime, his shop continued to trade and the UN and the Royal Project would, from time to time, ask him to take a new crop up the mountains — pumpkins, tomatoes, garlic, rice — some being adopted by his mountain friends, others cast aside. Being the only trader in the area, it was Teera’s task to continually find new markets for these new products.

“Dad was super creative,” smiled Naruemon, “when he couldn’t sell his beans to the merchants, he packaged them prettily with some hill tribe designs and sold them to the tourists. One year he discovered that there were many pine trees in the mountain villages, and the next thing we knew he was buying up tonnes of pine nuts, using his hill tribe ribbons, threads and material to decorate them and suddenly we were exporting them to the US as Christmas decorations!”

Putting Down Roots

“The south of Thailand had been growing Robusta coffee for a while but as we were in the highlands, the UN and the Royal Project began to explore Arabica, a variety much more suitable to this climate. Once they found a variety they were satisfied with, they came knocking and I thought, ‘uh-oh, here we go again!’ At that point I had never drunk a cup of coffee in my life, but I took some saplings and headed up to my villages, introducing them to this new crop. Then the UN pressured me to open the first coffee processing plant in Chiang Mai, so the Royal Project and I went halves on the costs of very expensive German machinery.”

When the first crop yielded, Teera bought five tonnes of coffee. Not knowing what to do with it all, and being the only trader in Chiang Mai, he sold some to Kasem Store, which supplied food products to the small number of expatriates at the time. It was a tiny outlet, so he headed to Bangkok to try to convince merchants there to try out this new coffee. Thai people had become used to traditional Thai coffee, a product of the Second World War when coffee was expensive. This coffee was mixed with a variety of grains including beans, wheat and corn, and was what Thais had come to associate with the taste of coffee. Introducing pure coffee to the Thai market was not just a sales and marketing task, but an entire cultural challenge. By 1991 Teera were selling 200 tonnes a year, thanks in large part to a large drinks corporation, who was asked by the United Nations to support this new industry.

In 2002, a change in CEO at a large drinks corporation, saw a 60 tonne order of coffee cancelled, and overnight Teera was bankrupt and in 20 million baht debt.

“I had studied marketing in Seattle and Portland in the US and had just returned home to teach post graduates at Payap University,” said Naruemon. “It was a tough decision, but my father needed me, so I quit my job and stepped in.”

Like Father like Daughter

Just as her father sacrificed his education to help his family following the tragic fire, Naruemon gave up her academic career when her father’s business faltered. Having lived in Seattle during the height of the Starbucks boom, she immediately saw the potential of coffee and with her marketing skills and following an analysis of the business’s recent bankruptcy, knew that she was not interested in being reliant on any one big business, but would prefer to be in a safer position working with a larger number of small businesses. She knew that soon Chiang Mai would be home to an abundance of coffee shops, and instead of opening one herself, made the wise decision to be in the business of helping other businesses; essentially the middle lady.

It took Naruemon just five years to pay off the family’s debt, and since then Hillkoff has expanded to become a multiple award-winning brand. Today, Hillkoff employs 140 people, has dealers in ten provinces all over Thailand as well as one in Malaysia, sells over 40 flavours of coffee — all Thai — and has three processing plants in the north.

“We have helped set up thousands of coffee shops over the past fourteen years,” she smiles happily, “And I am pleased that we have been such an integral part of the development of the love for coffee in Thailand.”

Waste Not Want Not

With success under her belt, Naruemon has, of late, focused her attention on her responsibilities to the planet. “Firstly we stand by Thai farmers, we don’t import any coffee at all,” she said. “Chiang Mai produces around 3,000 tonnes of coffee a year and it is pretty much all consumed here or within Thailand. We have been working closely with researchers on many projects. For instance we buy coffee waste from coffee shops and can now produce furniture or rubber-textured products which we sell. We are still experimenting with how to get the best value from our waste. Our roasting factory is the only one in the north which uses the wet scrubber system to preserve energy and reduce emissions. We have now measured all of our emissions and are working on a plan to offset all of it. The cherry pulp from coffee has also been studied and while it makes great fertiliser, the value is still not high, so we are now making tea out of it. We use every part of the coffee, and there is zero waste.

“Dad is still working hard, he helps oversee our coffee plantations and works with farmers. He had to close down the material shop two or three years ago because hill tribes dress like us now and don’t require his material anymore. And he has started his own construction firm, I am focused on expanding our business and working with researchers to make sure that we are as good to the environment as it has been to us.”

Naruemon has one big mission she says she still needs to work on, “People are not talking enough about Chiang Mai coffee in Chiang Mai; it is all Ethiopia this and Colombia that. I want Thai people to love coffee from our own country first.”