So, to your average farang it could seem strange that Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra’s resolve to end the sale of ivory in Thailand has come only now, when elephant populations are in mounting danger and Leonardo DiCaprio has started up a web petition. Why now? Hasn’t elephant conservation been important for years? Perhaps, but the issue isn’t as simple as it appears.

Internationally, the sale of ivory has been banned since the 1989 CITES convention. The ban was meant to slow the decline of the African elephant, a decline powered largely by the international ivory trade. In 1979, more than 1.3 million African elephants were recorded living in the wild; by the end of 1989, illegal poaching had pushed that number down to just 600,000. According to Lemieux and Clarke of the British Journal of Criminology, poachers in 1989 could receive more than $90 a pound for elephant ivory. The money was too good to ignore, and elephants were killed by the tens of thousands to keep up with demand. Figures today are difficult to track, but can reach over $1,000 per pound, depending on the quality and the marketplace.

For a while, the CITES ban seemed to work; the number of elephants roaming throughout Africa actually increased. Examination of data collected from 1979 to 2007, however, has made researchers less optimistic. While some African countries are experiencing resurgence in their elephant populations, others are lagging behind or even continuing to lose large numbers of animals. Why? Academics and conservation groups agree – the culprit is most likely still the ivory trade.

While CITES can make international decrees, it does not regulate markets within specific countries’ borders; individual nations are free to produce and sell ivory merchandise at will. These nations, however, are responsible for ensuring that the ivory in their internal markets is strictly domestic in order to discourage illegal poaching of the world’s endangered elephants. Countries hosting large internal ivory markets, such as China, Tanzania, and Thailand, represent potential profit for poachers anxious to launder illegally acquired raw materials past lax law enforcement.

Within Thailand, ivory is used primarily to create art pieces, some drawing from ancient traditions and others more modern. According to Thai law, these decorations can only be produced from the ivory of domesticated elephants that have died of natural causes. Documentation is required to prove that the ivory does not come from Thailand’s wild elephant population and that the elephant was not harmed for its ivory. Once the ivory is processed, the resulting products can only be legally sold to Thai nationals. In a country that values elephants so highly, for their beauty, their strength, and their place in the spiritual tradition, art created from the tusk of a domesticated elephant has the potential to act as a powerful tribute to the relationship between country and animal. Legally sourced ivory from elephants that led long comfortable lives can be made into protective amulets or traditional art pieces that have real cultural and spiritual value.

In an ideal world, the ivory trade would be both contained to Thailand and respectful of the living animal’s rights. The reality, of course, matches neither of these two criteria. According the New York Times, massive markets in China, where ivory chopsticks and figurines are highly prized, make ivory a valuable resource. For local vendors, foreign tourists to Thailand are a target; farang will often pay big money for elephant tusk trinkets, especially when fed a charming story about the long, happy life of the elephant in question.

While Thailand’s laws requiring documentation should ensure that the nation’s ivory is sourced morally, the Bangkok Post claims that laws are not strictly enforced. While there are only 67 authorised ivory retailers within Thai

borders, officials have found ivory trinkets everywhere from Bangkok’s massive Chatuchak Market to small tourist shops in Chiang Mai. In order to cash in on ivory’s popularity and keep up with demand, Thai ivory merchants are buying a lot of raw material, more material than is possible given the rate of natural death within Thailand’s domestic elephant population.

Environmental organisations, such as TRAFFIC, an NGO that monitors wildlife trade, have come to an obvious conclusion: at least some of that ivory is not legal. In fact, some of it isn’t even Thai. Thailand’s ivory economy is only legal as long as it is self-contained, but shrinking numbers of Asian elephants, attractive profits on ivory goods, and lax Thai law enforcement suggest that African ivory is being funneled into the ostensibly domestic market.

Respected environmental groups such as the Worldwide Wildlife Fund have reported that ivory laundering is an ever-increasing problem in Thailand and that an unknown amount of ivory is transported into the country from Africa each year. The ivory, usually taken from endangered elephants that are often brutally killed for their tusks, is smuggled into Thai workrooms where it is processed, presented to consumers and inspectors as “Thai,” and passed off as ethical.

Even within Thailand, according to the Bangkok Post, wild elephants are killed or maimed for their ivory. Their tusks are then sold and passed off as legal with forged domestication papers. Chasing big profits, corrupt ivory dealers work with poachers to circumvent laws that, by nature, limit the supply of ivory available.

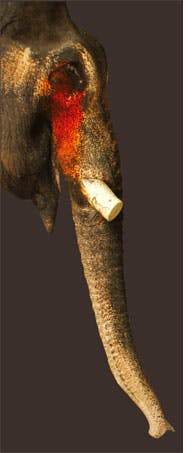

Soraida Salawala, founder of the Friends of the Asian Elephant Hospital in Lampang, has worked with elephants directly affected by the Thai ivory trade and knows that the market for ivory affects domesticated elephants as well.

Credits Wikimedia Commons / Rept0n1x

“In some cases, owners even cut the tusks themselves for fear that their elephants will die if a thief comes and cuts them,” she said. “Some owners need money and cut them off to sell by the kilogram.”

Reasons for tusk cutting vary; elephant conservationist Richard Lair, a California native who has lived and worked with elephants in Thailand for over 30 years, has seen elephants’ tusks trimmed or removed for a number of reasons, not all of them negative. “Some owners trim ivory from elephants’ tusks in order to make them less fragile,” he noted. “Tusks are also sometimes cut on especially aggressive elephants to protect the human beings who work with them. A shorter or blunter tusk is a less dangerous weapon.”

Though owners don’t intend to kill their elephants, removal of an elephant’s tusks is not without serious consequences. Inside of an elephant’s tusk is a pulp cavity, filled with sensitive tissue, blood vessels and nerves. Without sterile conditions and careful post-operative care, elephants suffer infections, loss of sensation, and severe pain. For elephants that suffer from complications, this practice can even be deadly.

Soraida has seen the consequences again and again at her hospital: “There have been many serious cases. Some suffered from tetanus after the tusks were cut off. We managed to save some but we could not reach others. The ones that we could not reach died from their infections.”

“Since March, I have not heard anything of the timeframe, nor anything constructive yet,” she commented. “But if we managed to slow the ivory trade, we could at least control the ivory in the market and discourage any new stock.”

While the Prime Minister’s pledge is only one small step towards the ultimate goal of protecting the world’s elephants, Soraida remains hopeful but realistic.

Tourists and residents can help push for more strict ivory regulation by refusing to purchase any ivory products in Thailand or abroad, by staying actively informed, and by donating to reputable elephant conservation organisations.

“Politicians tend to say things that are unrealistic, that aren’t going to happen, and that are much muddier than such clear statements support,” said an anonymous source who works with elephant conservation. “The Prime Minister’s statement is a step in the right direction, but the real big issue is that the African elephant trade is illegal, pure and simple, and Thailand has a clear obligation to stop it.”

For more information on the CITES ban and on the ivory trade in general, visit

www.cites.org and www.worldwildlife.org/species/elephant.

* Thank you Friends of the Asian Elephant for photo shoot location: www.elephant-soraida.com