As Western countries edge closer and closer to hemp and cannabis legalisation, Thailand is quietly and tentatively following suit. Following the vilification of cannabis and hemp caused by the American presence in the region in the late sixties, Thailand and her neighbours introduced harsh prison sentences, and even death penalties for the consumption and dealing of the drug. Almost half a century later, new, and more progressive attitudes are finally sprouting up like toadstools across Thailand. This year, laws have already been passed that will see hemp become a fully commercial crop within the next three years, and legislation regarding decriminalisation and re-classification of cannabis is currently under review, with positive results predicted within the next two years. Northern Thailand has been given the honour to lead the hemp revolution, with a rich history of cultivation among Hmong and other highland cultures making this the logical locale to begin, and starting with those who know best.

High Confusion

“The main problem we faced when trying to separate the legal status of hemp and cannabis was that the authorities didn’t understand the difference between the two plants,” explained Dr. Sarita Pinmanee, researcher and hemp project manager for the Highland Research and Development Institute (HRDI). “Hemp and cannabis are actually the exact same species, but hemp has been bred to contain less than 1% THC.”

THC is the psychoactive element of cannabis, and is what causes people to get high when they smoke the plant. Cannabis has an average of 20-30% THC content compared to hemp’s miniscule amount. “Ideally, we aim to keep the THC level lower than 0.3%,” said Wimol Punsupa, head of agronomy section of the Pang Da Royal Agricultural Station in Samoeng where hemp is currently being grown. “Without any THC, the plant is benign. And if smoked, all you will get is a bad headache,” he laughed as if from personal experience.

Until recently, Thai law failed to differentiate between the two crops in any way. “If you had any hemp product on you, you could be arrested and charged under drug laws,” laughed Dr. Sarita who pulled out a hemp wallet from her bag. “Technically, until early 2018, this is still illegal.”

Yet in comparison to other Southeast Asian countries, Thailand’s laws are proportionally relaxed. The strictest countries in the region include Indonesia, where over the last two years has seen the execution of 18 people for cannabis-related crimes, and the Philippines, which is currently summarily executing thousands of users and dealers through an extrajudicial drug war led by the right-wing president Rodrigo Duterte. Singapore and Brunei have the death penalty, and Malaysia issues a mandatory death sentence to anyone in possession of 200g or more. In comparison, Thailand only hands down death sentences to the biggest of smugglers, though it is universally understood that over 90% of those found guilty are generally the middle men who are later released under a royal clemency order. Possession leads to a maximum of 15 years in prison, and up to 100,000 baht in fines, but in reality the sentences are usually much shorter. Other countries such as Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam have harsh laws against cannabis and other drugs but rarely enforce them.

Royal Bud

“It was actually Her Royal Highness Queen Sirikit who kick-started Thailand’s hemp research and re-classification programme,” said Dr. Sarita. “In 2005, she visited the northern Hmong hill tribes and learnt about hemp and understood that these people needed some sort of protection to be able to continue using the crop to make clothes, ropes, trinkets and other important traditional items.”

Soon after that visit, hill tribe hemp loosely came under the protection of the Royal Projects on behalf of the HRDI. No longer could the police arrest and charge hill tribe villagers with cultivating illegal drugs if their land was under the protection of the Royal Projects, however any Hmong villages outside of the Royal Projects jurisdiction were still subject to the national laws — with arrests being made every year by overzealous police officers. “When I joined the HRDI as the Hemp Project Manager, I was often contacted by tribes’ people who were facing five, ten years in prison for growing hemp, but I was unable to help,” said Dr. Sarita. “That was back in 2009, but over the next four years we managed to get the ball rolling with a new interim law passed in 2013 that excluded hemp fibre and dried stalks from pentalty, enabling permit-free trade of the product with no fear of arrest which eased the pressure on the Hmong people.”

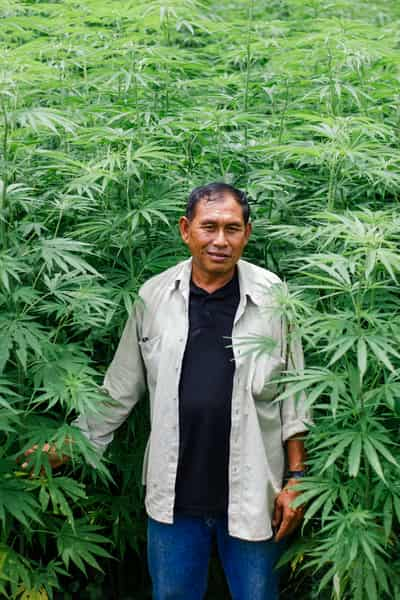

Over the next decade Dr. Sarita and her team of four fought for hemp to become legalised while continuing their research to create a taller hemp plant, with less THC and stronger fibres. “When we first started growing hemp, much of it has as much THC as cannabis, but we bred the THC out of it and encouraged the stalks to grow taller so that each hemp fibre extracted would be longer and stronger,” said Wimol Punsupa during a tour of his hemp plantation in Pang Da. “We have registered four new strains of hemp, RPF 1 – 4, all of which were bred from local hemp plants.”

Legalise It

It was in January 2017 that a law was finally approved and passed by the cabinet to legalise hemp with a THC level of 1% or lower for industrial and medical purposes. The ten page law, packed with eighteen clauses, limits hemp production to just 15 districts in six northern provinces; Chiang Mai, Chiang Rai, Nan, Tak, Phetchabun and Mae Hong Son. Most surprisingly, the law was supported by the country’s Office of the Narcotics Control Board (ONCB). “Any business will be able to apply for a permit, grow and produce hemp and hemp-based products starting in January 2018 when the law takes effect,” said Dr. Sarita. “However, clause 15 states that only state and state sponsored enterprises will be allowed to grow hemp with a permit in the first three years of the law coming into effect. This means that it will be 2021 before any private company can even apply for a permit.” In addition, several news sources have alleged that the Thailand Tobacco Monopoly have been granted exclusive rights to hemp, meaning all hemp products grown can only be sold to licenced tobacco factories. “This condenses the market and will prevent innovative businesses from having a chance to produce hemp,” concluded Dr. Sarita, disappointed by the provision but overall glad that the law has finally been passed.

When looking overseas to countries with a well-developed hemp industry, it is surprising that Thailand is slow to the game given their high quality natural hemp. Clothing, bags and basic medicines have been made from the hemp plant in highland communities for centuries, and with modern industrial techniques and machinery, high quality fibres can be made as fine as linen, opening up new possibilities for the clothing industry. The fibres can also be made into bioplastic and hemp concrete, and the inner stalk and seeds can be made into foods, essential oils, nutritional supplements, medicines and beauty products. “The hemp seed could be the world’s super food if it didn’t have such a bad stereotype,” added Dr. Sarita. “They contain 30% protein, 25% oil and carbohydrates. The oil is rich in Omega 3 and Omega 6, and if you take it regularly, you can really feel a difference in your brain.”

The Grass Ceiling

Yet despite all this positive momentum, there is one final hurdle that cannabis advocates will still struggle to jump. “Now we have legalised hemp, there is no need to carry on and legalise cannabis,” said Dr. Sarita when asked about cannabis legalisation, both medically and recreationally. “The Royal Projects were set up by the queen to provide an alternative to illegal drugs like opium and cannabis which were grown extensively across Thailand, to promote the legalisation of one of these drugs is against the MO. How could we ever support that?”

The irony seemed to be lost on Dr. Sarita as only several years earlier, hemp was just as illegal as cannabis, but that didn’t stop her team pushing for its legalisation. “Another issue is that people still see hemp as a drug, so we are losing support from the public and the government who are unaware of the differences, and we need to educate them first.” For the Hemp Research Department, the next step seems unclear. Hemp is legal and there are registered strains ready to be delivered, but Dr. Sarita insists that it is far from over. “Right now we are the only registered seed producer so I expect we will have our work cut out for us when all these new businesses begin ordering seeds.”

Despite her progressive mentality when it comes to hemp, Dr. Sarita still holds onto more traditional opinions when it comes to cannabis and those who smoke it. “People who smoke cannabis can’t function at work, are lazy and will get addicted,” she said. “We have yet to combat our drinking and smoking problem so adding another social issue to the mix would be idiotic.” Yet a movement of doctors in Thailand is trying to break this grass ceiling by starting their own movement — legal medical marijuana.

“Cannabis needs to be legalised for medical purposes,” insists Dr. Somnuek Siripantong, board member of the Association of Cell Therapy Thai (ACT Thai) public relations division. “There are already research centres set up in Rangsit University looking at the medical benefits of THC and CBD [Cannabidiol, a chemical in cannabis that makes up 40% of the plants extract and is the main ingredient in medical cannabis oils] and over 100 other chemicals specific to cannabis plants that all seem to play a part in curing certain diseases.”

A pilot clinic has already been set up in a Bangkok hospital, testing the success rates of using cannabis oil and other extracts in curing diseases such as Parkinson’s, epilepsy and cancer. More and more Thais are illegally importing cannabis oil and other supplements into the kingdom, risking long term prison sentences in order to better care for their loved ones.

At a cannabis conference in Bangkok held in early 2017 which was attended by the Food and Drug Administration and the ONCB, members of the public and medical experts made their cases for legalisation of cannabis for medical treatment. In a Coconuts TV documentary titled Highland, Pipop Chamnivikaipong, Deputy Secretary General of ONCB, said on record that “the method of using [cannabis] in medical treatments is of great importance in helping solve health issues in our country. Many prefer cannabis as a treatment for fatal diseases like cancer.” In addition, he went on record stating that it would take no longer than two years to legalise cannabis for medical treatment, saying clarifications will be made clear by the end of 2017. He even went on to suggest that recreational use is also under review, and a decision should be made within the next two years.

However, the overall opinion in the pro-medical marijuana community seems to fall short of recreational use. Dr. Somnuk suggests that Thailand has so many problems with intoxicants already, that giving them cannabis would only add fuel to the fire. A Chiang Mai advocate Dr. Prapatsorn Tipparat seconds this opinion, but suggests that although the evidence for medical marijuana is persuasive, she still feels that more research should be conducted before it is rolled out nationwide.

What is clear is that the medical community are yet to come to an overall consensus when it comes to the benefits of medical cannabis and whether it should be legalised or not. According to Dr. Somnuk, most disagreements come from a lack of education and the stereotypes that surround cannabis which are ingrained into society. What is certain however, is that when medical cannabis is legalised in Thailand, then there will be a medical tourism boom, with foreigners — and locals — seeking out affordable, cannabis related healthcare treatments in their thousands, and if Pipop Chamnivikaipong’s statements are accurate, we could see Thailand becoming the number one medical cannabis destination in as little as three or four years from now. Already, hemp legalisation feel like old news, and with three years to wait before private business can join the game, all eyes are now squarely on the cabinet, eagerly waiting for their next decision. Is a full cannabis revolution on the horizon or are we putting too many eggs in one hemp woven basket?